Towards a Critical Faculty

2007

I initially described this as “a short [!] reader concerned with art/design education” that I compiled for the Academic Project Office (APO), a lively but short-lived initiative set up at Parsons The New School in New York by Tim Marshall and Lisa Grocott around the mid-2000s. It was published as a pamphlet to be read by the school’s entire Liberal Arts faculty, with the aim of provoking a school-wide discussion.

At some point along the way, I decided it ought to become the first of three documents, whose individual titles would join up into one long composite—an idea stolen from B.S. Johnson. At this point I had no idea what that sentence might be, so I left the first part open-ended enough to allow further clauses to be clipped on later, which turned out to be (Only an Attitude of Orientation) and From the Toolbox of a Serving Library.

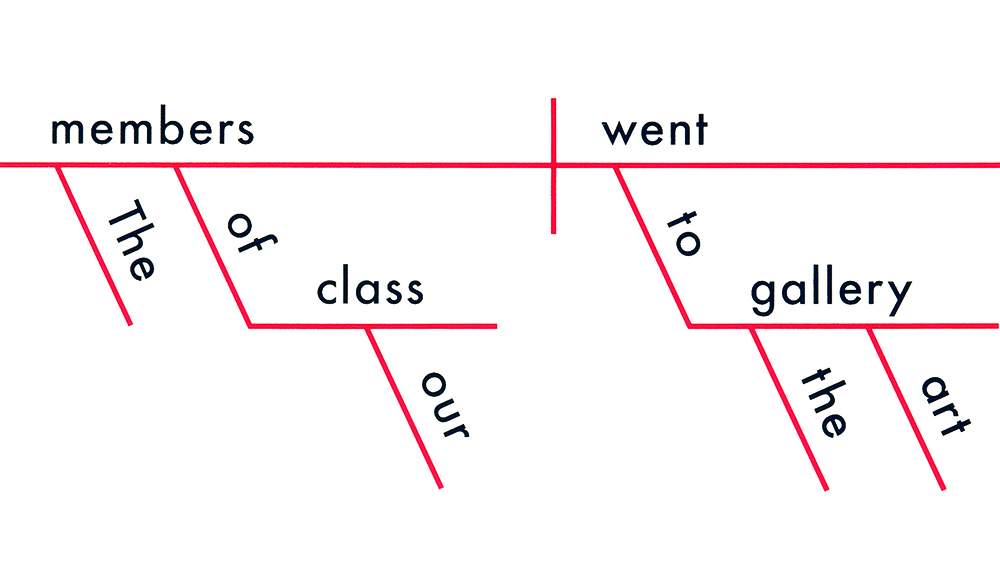

Lead image: Diagrammed sentence made with Frances Stark, 2006.

*

Let me open this slightly odd document by introducing myself through my own art-educational background. I began as an undergraduate student of Typography & Graphic Communication in a rigorous but essentially maverick department at The University of Reading in the UK, then later as something between graduate and apprentice at the familial Werkplaats Typografie [Typography Workshop] in the provincial Netherlands. Since then I have worked across the arts, mainly as a book designer, co-founded and edited a design journal, Dot Dot Dot, which continues in an ever-widening cultural vein, and simultaneously taught in the undergraduate departments at both my old Reading course and at the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. After a few years teaching, I recently came to a standstill. I found myself so confused about what and why I was teaching that it seemed better to stop and readdress the point before trying again. Around this time I also found myself involved in countless conversations with friends and colleagues in similar situations with similar feelings, marked less by disillusion and more by confusion. Since then I have been involved in one-off engagements at MIT, SVA, Yale, Art Center and USC, and most recently have ended up as some kind of wild card in Parsons’ new-founded Academic Project Office (APO), who are interested in addressing the same concerns. Which is how I come to be attempting to engage you in the process.

Let me open this slightly odd document by introducing myself through my own art-educational background. I began as an undergraduate student of Typography & Graphic Communication in a rigorous but essentially maverick department at The University of Reading in the UK, then later as something between graduate and apprentice at the familial Werkplaats Typografie [Typography Workshop] in the provincial Netherlands. Since then I have worked across the arts, mainly as a book designer, co-founded and edited a design journal, Dot Dot Dot, which continues in an ever-widening cultural vein, and simultaneously taught in the undergraduate departments at both my old Reading course and at the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. After a few years teaching, I recently came to a standstill. I found myself so confused about what and why I was teaching that it seemed better to stop and readdress the point before trying again. Around this time I also found myself involved in countless conversations with friends and colleagues in similar situations with similar feelings, marked less by disillusion and more by confusion. Since then I have been involved in one-off engagements at MIT, SVA, Yale, Art Center and USC, and most recently have ended up as some kind of wild card in Parsons’ new-founded Academic Project Office (APO), who are interested in addressing the same concerns. Which is how I come to be attempting to engage you in the process.A first disclaimer: This document is a loose, fragmented reader designed to circle the area the APO team intends to discuss in subsequent forums, both inside and outside the context of The New School. Because the topic is so broad and quickly overwhelming, it seems most useful by way of introduction to simply assemble my personal collection of other people’s thinking on the subject past and present, with a view to the future. This is a brief survey based on resources within easy reach and a few months’ worth of casual discussion. It maps the lay of the land as a work-in-progress intended to be amended, added to, and refined. One advantage of this approach is that it ought to remain timely.

A second disclaimer: The entire issue of art/design schooling is infuriatingly elliptical and constantly in danger of canceling itself out. This is, at least in part, because what we might initially perceive to be separable issues (the distinctions between undergraduate and graduate, art and design, teaching and learning, mentor and facilitator, etc.) are all inextricably entwined. Once one is addressed, one or more of the others inevitably come into play. This is why the present document is not particularly subdivided; even its basic chronological divisions barely hold.

Artists and designers (or good ones) are by nature reflexive creatures—they simultaneously reflect on what they do while doing it. As I understand it, the APO was explicitly set up to harness this quality towards a practical end: to engage its design faculty in actively designing the institution—a logic that seems as paradoxically rare as it is obvious in contemporary art/design schools. In order to dismantle a few anticipated responses, then: this is not a rooting-out exercise, nor a preamble to a series of job losses (probably the opposite), nor a change for the sake of change, nor some infant generation staking a claim, nor a gratuitous exercise in spending excess money, nor a hollow PR campaign. It simply proposes the time, space and energy to ask the sorts of questions that should be permanently addressed as a matter of course, with the school set up to accommodate them as and when necessary. In short, to engage our “design thinking” towards consolidating a future curriculum. The principal obstruction to such constructive intentions lies in the disjunct between the academic and financial-bureaucratic divisions of contemporary schools—between projected ideas and “reality.” I see no good reason why the two can’t be resolved together in a plan that is at once transparent, open and clear.

There are countless routes into thinking about teaching contemporary art/design. Mine is to try to get to the bottom of a term just mentioned, and which is constantly floating around at Parsons: “design thinking.” First by questioning the meaning of the phrase itself, which is perhaps the first clue to my background and approach. “Design thinking,” to my mind, is a tautology; designing is synonymous with thinking (“to conceive or fashion in the mind,” according to the dictionary). That said, I understand the implication: “design thinking” (more or less interchangeable with “intelligence” or “expertise”) alludes to the field’s fundamental mode of approach as distinct from that of other fields, such as “craft thinking,” “scientific thinking” or “philosophical thinking.”

In my view, then, the key characteristic of “design thinking” can be defined as “reflection-in-action,” which Norman Potter further elucidates in his statement:

Design is a field of concern, response, and enquiry as often as decision and consequence. (Potter, 1989)

The perceived payoff of unpacking “design thinking” is that its constituent qualities can be identified and extracted to provide the new focus of a contemporary art/design curriculum. This follows from the common intuition that existing models are incapable of accommodating the ever-blurring boundaries of art/design disciplines, of specialism giving way to generalism. The idea is that this so-called design thinking is transferable (or “exportable”) across disciplines, and so students ought to be taught to develop a general reflexive critical faculty rather than discipline-specific skills.

Here I propose to consider the pedagogical application of “design thinking” through my own form of design thinking (“concern, response, and enquiry”). I will rewind, then pause, then fast-forward, plotting the historical trajectory of art/design education in the hope of identifying how and why past models were set up in response to prevailing social conditions, then articulating why, in light of these legacies, along with an overview of the present paradigm, “design thinking” might indeed be an appropriate foundation for the future. In other words, for the length of this pamphlet at least, I’m giving the idea the benefit of my doubt.

Who really can face the future? All you can do is project from the past, even when the past shows that such projections are often wrong. And who really can forget the past? What else is there to know? What sort of future is coming up from behind I don’t really know. But the past, spread out ahead, dominates everything in sight. (Pirsig, 1974)

...

PAST

What are the extant models of art/design schools? Let’s try to compile a lineage starting around a hundred years ago when, in the wake of the industrial revolution, such schools were first set up as discrete entities. The first key distinction was between the traditional master-apprentice model for craft-based professions (metallurgy, carpentry, etc.), and the academy-studio model for fine art training (drawing, painting, etc.)

The School of Arts and Crafts was set up in 1896 to fill “certain unoccupied spaces in the field of education.” The foundation of the School represented an important extension of the design philosophy of the Arts and Crafts movement which, largely inspired by William Morris, had raised the alarm against the lowering of standards as a result of the mechanization of design processes. Advocating a return to hand-production, this movement argued that the machine was a social evil. The School’s first principal believed that “science and modern industry have given the artist many new opportunities” and that “modern civilization rests on machinery and that no system for the encouragement or endowment of the arts can be sound that does not recognize this.”

The School proved to be innovatory in both its educational objectives and its teaching methods. “The special object of the School is to encourage the industrial application of decorative design, and it is intended that every opportunity should be given for pupils to study this in relation to their own particular craft. There is no intention that the school should supplant apprenticeship; it is rather intended that it should supplement it by enabling its students to learn design and those branches of their craft which, owing to the sub-division of the processes of production, they are unable to learn in the workshop.”

The majority of the staff of the school were not “certificated,” full-time teachers; rather were they successful practitioners in their respective crafts, employed on a part-time basis, and providing the school with a great variety of practical skills and invaluable contacts with the professional world of the designer and craftsman. These pioneering innovations in objective and method proved to be crucial to a philosophy of art and design education which fashioned the establishment and development of many similar institutions in Britain and abroad, including the Weimar Bauhaus. (Central School prospectus, London, 1978)

In describing this office and project to other people, I invariably find myself back at the Bauhaus, simply because it remains the most explicit representation of a set of coherent principles and marker of a paradigm shift. Namely: the switch from the traditional master-apprentice to the group-workshop model; the introduction of the foundation course of general principles for all fields; the application of fine art to practical ends; and the synthesis of the arts around one particular vision. Whether these ideas were actually realized or even consistent is irrelevant here; they endure as what the Bauhaus has come to represent.

Workshops, not studios, were to provide the basis for Bauhaus teaching. Workshop training was already an important element in the courses offered by several “reformed” schools of arts and crafts elsewhere in Germany, but what was to make the Bauhaus different from anything previously attempted was a tandem system of workshop-teaching. Apprentices were to be instructed not only by “masters’ of each particular craft but also by fine artists. The former would teach method and technique, while the latter, working in close cooperation with the craftsmen, would introduce the students to the mysteries of creativity and help them achieve a formal language of their own. (Whitford, 1984)

From here we can then ask: Are art schools in the 21st century still based on the Bauhaus model? If so, is this still relevant almost a century later? If not, on what other model(s) are they based, if at all? If not based on a model, how are they designed, or how do they otherwise come into being? And finally: Whether based on a model or not, should they be?

The old art schools were unable to produce this unity; and how, indeed, should they have done so, since art cannot be taught? Schools must be absorbed by the workshop again.

Our impoverished State has scarcely any funds for cultural purposes any more, and is unable to take care of those who only want to occupy themselves by indulging some minor talent. I foresee that a whole group of you will unfortunately soon be forced by necessity to take up jobs to earn money, and the only ones who will remain faithful to art will be those prepared to go hungry for it while material opportunities are being reduced, intellectual possibilities have already enormously multiplied. (Gropius, 1919)

And really, following the various subsequent incarnations of the Bauhaus in Germany (and the couple of postwar offshoots in Chicago and Ulm), any sense of an explicit, shared pedagogical ideology tails off here, coinciding with the Second World War and the end of what is generally regarded as the heroic phase of modernism.

I also once dreamed of a school where it would be natural to expect such an intermix of professions, arts and trades. There was some attempt in Lethaby’s early ideas for the Central School of Arts & Crafts in London, in Henry vande Velde’s and Gropius’s Weimar Bauhaus-Hochschule für Gestaltung, and at the Ulm Hochschule für Gestaltung. The two latter did not survive: the Central transformed itself into a School of Art & Design, only distinguishable from many others by some still-surviving tradition, and, as always, everywhere, by occasional concatenations of firing staff & students.

All art schools, until some years ahead, have tried to teach what teachers taught, or else supplied an environment to expand. (And I can’t think it very bad to give a human being three or four years of freedom to work out what consequence or nonsense his desires at eighteen/nineteen are; by “his” I include unisex “hers.”) The question now is, not only the structure of art education, nor indeed the government reports, but, very strictly, what should we teach, what should they learn; also how can they be educated. There is no way to teach anything except through personal contact and conduct. There is no way to teach any person who lacks desire. There is no way to teach through excessive specialization in an “art” subject, with an iced-on gloss of general-liberal-complementary studies. Because the “subject” and its complement belong together. It should not prove impossible to give the “art” ones jobs .... (Froshaug, 1970)

Through the 1960s and 1970s—and on into postmodernity—the art/design school was increasingly characterized by the creation and popularization of its own image and social codes (bound up with the various facets of youth liberation, its movements and nascent culture). This was school conceived as a liberal annex and breeding ground, but whose by-product was the acceleration of animosity towards the so-called Real World of business.

The art school has evolved through a repeated series of attempts to gear its practice to trade and industry to which the schools themselves have responded with a dogged insistence on spontaneity, on artistic autonomy, on the need for independence, on the power of the arbitrary gesture. Art as free practice versus art as a response to external demand: the state and the art market define the problem, the art school modernizes, individualizes, adds nuance to the solution.

Art school students are marginal, in class terms, because art, particularly fine art, is marginal in cultural terms. Constant attempts to reduce the marginality of art education, to make art and design more “responsive” and “vocational” by gearing them towards industry and commerce have confronted the ideology of “being an artist,” the romantic vision which is deeply embedded in the art school experience. Even as pop stars, art students celebrate the critical edge marginality allows, turning it into a sales technique, a source of celebrity. (Frith/Horne, 1987)

The following account was written by a student towards the end of this era—a typically convoluted attempt to deal with the contradictions of lingering socialist ideals amid burgeoning social liberation and commercialization:

I am trying to learn to be a designer. Designers are directly concerned with life. Designs are for living. Designing is just part of the process in which solar energy lives through the medium of hereditary information. Designers are concerned with information—information which furthers life. Being a designer is finding out ways of furthering life. Not thermodynamicsmechanics life, this is being a doctor, a servant purely. Emotion-communion life. How you check a design: does it make its user more alive? Or his children maybe? We have to work in time also.

Here is a problem for the designer, one to beat his head against. Clients usually ask him to operate the other way—against life—the clients I have come across. They ask him usually to make a design for part of a system for making a profit. Making a profit is life, sure, but for the client only. And it may be the client the designer is working for, but it is people he is working on. The client doesn’t sit down and read all his 50,000 leaflets, people do. The client pays, but the designer must be ready to tear up his cheq-ues if he or other people he loves don’t or won’t get the money, and if the client is trying to use him to channel life away from other people. The designer is working on people: he is working for people.

The designer may have to work for clients whose business is drainage of this kind. But not if he can survive without. If he has to, he must never forget what they are doing, and what they are doing to him, what they are asking him to do to other people. If he forgets this for a moment, they may start draining him. There must be people who are working for people. He can work for them. Then he will be a real designer, designing for life, not death.

How? I don’t know yet, that’s why I go to school, to experience, to share experience with those to whom these problems are no longer new and with those to whom their very newness is an opportunity for living. (Bridgman, 1969)

...

PRESENT

—and this is the same writer forty years on:

We were wrong. That old article tells you why: rational design would only work for rational people, and such people do not exist. Real people have irrational needs, many of them to do with human tribalism. Though tribalism itself is rational—it increases your chances of survival—its totems are not. If you belong to the coal-effect tribe, you’ve got to have a coal-effect fire. There’s no reason for wanting your heat source this shape, other than the fact that other tribe members do. There’s no reason for having a modernist, post-modernist, minimalist or any other source of heat source, either, except as a similar totem. The reasons have to be tacked on later (but only if you are a member of the rationalist tribe—nobody else bothers).

So designers can’t rule the world, they can only make it more like it already is. Fortunately (or unfortunately if you’re a hard-line rationalist) the world is not any kind of coherent entity, so “like it already is” can mean many different things—just choose your tribe and go for it. This can give a satisfying illusion of control, despite the strict limits imposed by tribal convention. Because many tribes have novelty as one of their totems, it is possible to change—“redesign”—some of the other totems at regular intervals. Once confined to the clothing industry, this kind of programmed totemic change now extends to goods of all kinds: “fashion designers” have become just “designers.”

Such designers—the ones who design “designer” goods—have apparently achieved a measure of control over the wider public. It seems, according to one TV commercial I have seen, that they can even make people ashamed to be seen with the wrong mobile phone—a kind of shame that can only have meaning within a designer-led tribal context. The old, Marxist-centralist kind of designer didn’t care whether people felt shame or anything else. He or she simply knew what was “best” in some absolute sense, and strove to make industry apply this wisdom. But “designer” designers work the other way around. Far from wanting to control their commercial masters, they enthusiastically share their belief that the public, because of its irrepressible tribal vanities, is there to be milked. They have capitulated in a way that my [previous] article fervently hoped they would not, but for the reason that is pointed out: in visual matters there is no “one best way.” Exploiting this uncertainty is what today’s design business is all about. The old, idealistic modernism that I once espoused is on the scrap heap.

So my naive idea of the 1960s—that designers were part of the solution to the world’s chaotic uncontrollability—was precisely the wrong way round. Today’s designers have emerged from the back room of purist, centralist control to the brightly lit stage of public totem-shaping. Seen from the self-same Marxist viewpoint that I espoused in those ancient days, they are now visible as part of the problem, not the solution. They have overtly accepted their role as part of capitalism. Designers are now exposed, not as saviours of the planet but as an essential part of the global machinery of production and consumption. (Bridgman, 2002)

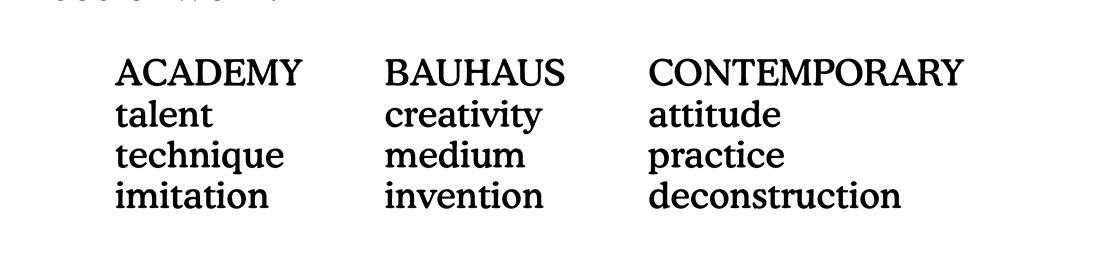

Thierry de Duve has identified and calibrated the component qualities of three fundamental paradigms that underly models on which art schools have been defined: the ACADEMY, the BAUHAUS, and what I propose to simply call the CONTEMPORARY.

The ACADEMY describes the pre-modernist period roughly up until the First World War. It is based on the idea of students possessing unique talent specific to a discipline. It is taught through the education of technique, abiding a historical chain of development. And its method of teaching is by imitation, involving the reproduction of sameness in view of continuing and developing a particular discipline.

The BAUHAUS, by comparison, describes the period roughly between WWI and WWII. It can be considered modernist inasmuch as it explicitly breaks from predominantly romantic or classical ways of working and thinking, and remains the foundation of most art/design schools in existence today —“often subliminally, almost unconsciously … more or less amended, more or less debased,” according to De Duve. It is based on the idea of students possessing a general creativity that spans disciplines. It is taught through the education of a medium as an autonomous entity, without emphasizing its lineage. And its method of teaching is by invention, involving the production of otherness and novelty. As such, it emphasizes formalism.

The CONTEMPORARY describes the prevailing condition which, although underlying the art/design world as a paradigm equivalent to (yet distinct from) the previous two, has yet to yield widespread collective change in the way its schools are constructed. Present-day ideas tend to be poured into the existing Bauhaus container, but they no longer fit. Calibrated in line with the other models, the contemporary tendency holds that students possess a general attitude that spans disciplines. It is taught through the education of a practice through which this attitude is articulated. And its method of teaching is by deconstruction, involving the analysis of a work’s constituent parts. Although the term “desconstruction” is open to misunderstanding in light of its various common formal associations (particularly in Architecture), I prefer to keep De Duve’s chart intact and emphasize that his “deconstruction” refers to the intellectual unpacking, dismantling, and reading of a given piece of work.

The back-end of this period—which brings us roughly up to date—has been further marked and marred, of course, by the propagation of school as business, student as customer, and all the attendant bureaucracy that instigates the ever-increasing gap between actual pedagogy and its marketed image.

Accreditation is an attempt to communicate to the world that we know and agree on what the truth is. But no school ever believes in the generic principles it must appear to endorse to be accredited. Those who draft these supposedly shared principles are not those known for their creativity or their knowledge of the history of the art they are trying to protect. Accreditation processes are universally discredited yet ever more intrusive. Kafka as the descendant of Vitruvius. (Wigley, 2005)

The fraying of any coherent consensus since the Bauhaus, further confused by the fact that policies are increasingly determined by schools’ financial departments rather than academic ones, has resulted in a largely part-time generation of itinerant teaching staff who lack the opportunities (time, energy, resources, community, encouragement, inclination) to engage in theoretical or philosophical grounding, while—as far I can see—needing and wanting one.

Now, if we accept all this as given and zoom out of the specific focus on schools for a moment, let’s try to summarize those current social conditions directly related to art and design, on which we might found a new protocol.

Alain Findeli defines the contemporary paradigm—“shared beliefs according to which our educational, political, technological, scientific, legal and social systems function”—as comprising three key characteristics: Materialism, Positivism, and Agnosticism. He then lists the morbid tendencies of the sort of design culture that currently flourishes under such preconditions:

The effect of product engineering and marketing on design, i.e., the determinism of instrumental reason, and central role of the economic factor as the almost exclusive evaluation criterion.

An extremely narrow philosophical anthropology which leads one to consider the user as a mere customer or, at best, as a human being framed by ergonomics and cognitive psychology.

An outdated implicit epistemology of design practice and intelligence, inherited from the nineteenth century.

An overemphasis upon the material product;

an aesthetics based almost exclusively on material shapes and qualities.

A code of ethics originating in a culture of business contracts and agreements; a cosmology restricted to the marketplace.

A sense of history conditioned by the concept of material progress.

A sense of time limited to the cycles of fashion and technological innovations or obsolescence.

Having mapped these bleak circumstances, he then asks:

What could be an adequate purpose for the coming generations? Obviously, the environmental issue should be a central concern. But the current emphasis on the degradation of our biophysical environment tends to push another degradation into the background, that of the social and cultural environments, i.e. of the human condition. (Findeli, 2001)

—and suggests that one key appropriate shift, already underway, is precisely that of dematerialization, away from a “product-centered attitude.” This implies the end of the product-as-work-of-art, heroic gesture, genius mentality and fetishism of the artifact. A more appropriate approach would focus more on the human context of the design “problem”; it would emphasize the design of services—whether post offices, hospitals, web providers, or indeed school bureaucracies—rather than material products; and in the face of overproduction and planned obsolescence, the systems that supplant the “vanishing product” would be approbated on sustainable, ecological grounds.

Let’s counteract this material depression with the optimistic abstraction of Italo Calvino’s set of lectures, Six Memos for the Next Millennium—a concise inventory of contemporary qualities and values that he proposed ought to be carried over the threshold of 2000 (written about 15 years in advance). These lectures directly referred to literature, specifically the continuing value of the novel, and as such consist mainly in examples drawn from a gamut of high-flown literary history from Lucretius to Perec. The qualities are, however, easily transposed across disciplines, and thus exemplify both “design thinking” and at least three of Calvino’s themes (lightness, quickness, multiplicity).

To summarize, Calvino first propagates LIGHTNESS, describing the necessity of the facility to “change my approach, look at the world from a different perspective, with a different logic and with fresh methods of cognition and verification.” He cites Milan Kundera’s conception of The Unbearable Lightness of Being in desirable opposition to the reality of The Ineluctable Weight of Living, and draws a parallel with the two industrial revolutions, between the lightness of “bits” of information travelling along circuits and the heaviness of wrought iron machinery. The second quality, QUICKNESS, summarizes economy of expression, agility, mobility and ease. He quotes Galileo’s notion that “discoursing is like coursing”—reasoning is like racing—and that “For him good thinking means ... agility in reason, economy in argument and ... imaginative examples.” The third is EXACTITUDE, as opposed to the “plague afflicting language, revealing itself as a loss of cognition and immediacy, an automatism that tends to level out all expression into the most generic, anonymous and abstract formulas, to dilute meanings, to blunt the edge of expressiveness ….” While Calvino admits that precision and definition of intent are obvious qualities to support, he argues that the contemporary ubiquity of language used in a random, approximate, careless manner, is extreme enough to warrant the reminder. Next comes VISIBILITY, in which the author tackles the slippery nature of imagination, particularly the difference between image and word as the primary source of imagination, and whether imagination as such might be considered foremost either an “instrument of knowledge” or “identification with the world soul.” Alongside these two definitions, Calvino offers a third: “the imagination as a repertory of what is potential, what is hypothetical … the power of bringing visions into focus with our eyes shut, of bringing both forms and colours from the lines of black letters of a white page, and in fact thinking in terms of images.” Finally, MULTIPLICITY refers to “the idea of an open encyclopedia, an adjective that certainly contradicts the noun encyclopedia, which etymologically implies an attempt to exhaust knowledge of the world by circumscribing it, but today we can no longer think in terms of a totality that is not potential, conjectural, and manifold.” This fifth memo promotes perhaps the most obvious of contemporary tropes, the network. The sixth, CONSISTENCY, was unrealized at the time of Calvino’s death.

Throughout his attempt to grasp his precise relationship to these nascent traits, Calvino constantly invokes polar opposites.The most memorable and profound of these is the dualism of syntony and focalization—active participation in the world versus constructive meditation on it. The struggle to balance the two, he says, is prerequisite for the creation of culture. Brian Eno has proposed that it’s more profitable to think in terms of continuums, greyscales, or axes between concepts than the usual binary poles (whether Neat vs. Shaggy hairstyles, Capitalism vs. Communism, or Us vs. Them):

Let’s start here: “culture” is everything we don’t have to do. We have to eat, but we don’t have to have “cuisines,” Big Macs or Tournedos Rossini. We have to cover ourselves against the weather, but we don’t have to be so concerned as to whether we put on Levi’s or Yves Saint-Laurent. We have to move about the face of the globe, but we don’t have to dance. These other things, we choose to do. We could survive if we chose not to.

I call the “have-to” activities functional and the “don’t-have-to”s stylistic. By “stylistic” I mean that the main basis on which we make choices between them is in terms of their stylistic differences. Human activities distribute them on a long continuum from the functional (being born, eating, crapping and dying) to the stylistic (making abstract paintings, getting married, wearing elaborate lace underwear, melting silver foil onto our curries).

The first thing to note is that the whole bundle of stylistic activities is exactly what we would describe as “a culture”: what we use to distinguish individuals and groups from each other. We do not say of cultures “They eat,” but “They eat very spicy foods” or “They eat raw meat.” A culture is the sum of all the things about which humanity can choose to differ—all the things by which people can recognize each other as being voluntarily distinguished from each other.

But there seem to be two words involved here: culture, the package of behaviors-about-which-we-have-a-choice, and Culture, which we usually take to mean art, and which we tend to separate as an activity. I think these are connectable concepts: big-C Culture is in fact the name we reserve for one end of the FUNCTIONAL/STYLISTIC continuum—for those parts of it that are particularly and conspicuously useless, specifically concerned with style. As the spectrum merges into usefulness, we are inclined to use the words “craft” or “design,” and to accord them less status, and as it merges again into pure instinctual imperative we no longer use the word “culture” at all. From now onwards, when I use the word “culture” I am using it indiscriminately to cover the whole spectrum of activities excluding the “imperative” end. And perhaps that gives us a better name for the axes of this spectrum: “imperative” and “gratuitous”—things you have to do versus things you could choose not to do. (Eno, 1996)

I’d contend, then, that what ought to preoccupy entire faculties as well as individual teachers, is understanding where on this sliding scale they exist—then working out where they should exist. Ought their teaching be oriented more towards small-c culture or big-C Culture? I don’t mean to insinuate a simplistic, reductive value judgement, but consider these two inventories:

There are many roles for designers even within a given sector of professional work. A functional classification might be: Impresarios: those who get work, organize others to do it, and present the outcome. Culture diffusers: those who do competent work effectively over a broad field, usually from a stable background of dispersed interests. Culture generators: obsessive characters who work in back rooms and produce ideas, often more use to other designers than the public. Assistants: often beginners, but also a large group concerned with administration and draughtsmanship. Parasites: those who skim off the surface of other people’s work and make a good living by it. (Potter, 1969)

and:

Every one of them does many things well but one best: Each represents an archetype who builds a culture of creativity in a specific way. There is The Talent Scout, who hires the über-best and screens ideas at warp speed. The Feeder, who stimulates people’s minds with a constant supply of new trends and ideas. The Mash-up Artist, who tears down silos, mixes people up, and brings in outside change agents. The Ethnographer, who studies human behavior across cultures and searches for unspoken desires that can be met with new products. The Venture Capitalist, who generates a diversified portfolio of promising ideas that translate into new products and services. (Conlin, 2006)

While both seem to reasonably summarize the roles that could usefully inform contemporary design (or “communication” or whatever) courses, and the sort of specializations that might replace traditional streaming, it’s worth pointing out that the rhetoric and attitude of the first is geared towards accommodating demand, concerned with some vestige of imperative needs while that of the second is geared towards creating demand, which doesn’t pretend to fulfill anything other than gratuitous needs. In other words, the former attempts to maintain (big-C) Constructive principles, while the latter is resolutely resigned to (small-c) commodification. Again: consider where on the axis we currently stand, and where might we reasonably slide to—on both practical and ethical terms.

...

FUTURE

If students [teachers] feel blocked by society as it is, then they must help find constructive ways forward to a better one. In a personal way, the question must be answered by individual students [teachers] in their own terms, but as far as design goes, it is possible to see two slippery snakes in the snakes and ladders game. The first snake is to suppose that the future is best guaranteed by trying to live in it; and the second is an assumption that must never go unexamined—that the required tools of method and technique are more essential than spirit and attitude. This snake offers a sterility that reduces the most “correct” procedures to a pretentious emptiness, whether in education or in professional practice. The danger is reinforced by another consideration. There can be a certain hollowness of accomplishment known to a student [teacher] in his own heart, but which he is obliged to disown, and to mask with considerations of tomorrow, merely to keep up with the pressures surrounding him. Apart from the success-criteria against which his work may be judged, there is a more subtle and pervasive competitiveness from which it is difficult to be exempt, even by the most sophisticated exercises in detachment. Hence the importance of recognizing that education is a fluid and organic growth of understanding, or it is nothing. Similarly, when real participation is side-stepped, and education is accepted lovelessly as a handout, then reality can seem progressively more fraudulent.

Fortunately, the veriest beginner can draw confidence from the same source as a seasoned design specialist, once it is realized that the foundations of judgement in design, and indeed the very structure of decision, are rooted in ordinary life and in human concerns, not in some quack professionalism with a degree as a magic key to the mysteries. From then on, to keep the faith, to keep open to the future, is to know the present as a commitment in depth, and to know the past where its spirit can still reach us. (Potter, 1969)

With all this in mind, can we rethink a curriculum that could realistically address the conditions variously described above (in more or less overlapping ways), fully aware of past attempts, which avoids the easy slide into trite idealism or, equally, marketing rhetoric, and isn’t necessarily crowd-pleasing; a proposal that offers a grounding for art/design teachers to comprehend and be able to articualte why, how, and towards what ends they are teaching; and that does so by tackling the current mis-alignment of models head-on, from the actual core of the institution, and with long-term foresight instead of the more familiar sense of temporarily shoring up the problem …?

A proper response requires answering the following questions honestly and explicitly, with concrete justifications and examples:

Is it necessary and desirable to cultivate an increasingly generalized, inherently cross-disciplinary art/design education?

Why?

Is it necessary and desirable to more broadly encompass of other social studies in art/design education?

Why?

Should a curriculum be predominantly geared towards

1. questioning, 2. fulfilling, or 3. creating

a. social needs, or b. commercial demands?

Why?

We no longer have any desire for design that is driven by need. Something less prestigious than a “designed” object can do the same thing for less money. The Porsche Cayenne brings you home, but any car will do the same thing, certainly less expensively and probably just as quickly. But who remembers the first book, the first table, the first house, the first airplane? All these inventions went through a prototype phase, to a more or less fully developed model, which subsequently became design. Invention and the design represent different stages of a technological development, but unfortunately, these concepts are being confused with one another. If the design is in fact the aesthetic refinement of an invention, then there is room for debate about what the “design problem” is. Many designers still use the term “problem-solving” as a non-defined description of their task. But what is in fact the problem? Is it scientific? Is it social? Is it aesthetic? Is the problem the list of prerequisites? Or is the problem the fact that there is no problem? (Van der Velden, 2006)

Perhaps contemporary art/design teaching indeed implies less “problem solving” and more a kind of social philosophy, as suggested here—with admittedly simplistic polarity—by Emilio Ambasz:

The first attitude involves a commitment to

design as a problem-solving activity, capable of formulating, in physical terms, solutions to problems encountered in the natural and socio-cultural milieu. The opposite attitude, which we may call one of counter-design, chooses instead to emphasize the need for a renewal of philosophical discourse and for social and political involvement as a way of bringing around structural changes in our society. (Ambasz, 1972, quoted in Van der Velden, 2006)

—which is more or less confirmed here:

Education is all about trust. The teacher embraces the uncertain future by trusting the student, supporting the growth of something that cannot yet be seen, an emergent sensibility that cannot be judged by contemporary standards. A good school fosters a way of thinking that draws on everything that is known in order to jump energetically into the unknown, trusting the formulations of the next generation that by definition defy the logic of the present. Education is therefore a form of optimism that gives our field a future by trusting the students to see, think and do things we cannot.

This optimism is crucial. The students arrive from around 55 different countries with an endless thirst for experimentation. It is not enough for us to give each of them expertise in the current state-of-the-art. We have to give them the capacity to change the discipline itself, to completely define the state-of-the-art. More than simply training the architects how to design we redesign the very figure of the architect. The goal is not a certain kind of architecture but a certain kind of evolution in architectural intelligence.

The architect is, first and foremost, a public intellectual, crafting the material world to communicate ideas. Architecture is a way of thinking. By thinking differently, the architect allows others to see the world differently, and perhaps to live differently. This perhaps is crucial. For all the relentless determination of our loudest architects and their most spectacular projects, architecture dictates nothing in the end. The real gift of the best architects is to produce a kind of hesitation in the routines of contemporary life, an opening in which new potentials are offered, new patterns, rhythms, moods, pleasures, connections, perceptions ... offered as a gift that may or may not be taken up. (Wigley, 2006)

Following the line of many discussions I’ve had with colleagues, I’d suggest that one practical way of proceeding is to directly reconsider the relevance of that Bauhaus-derived skill-based workshop/studio teaching, if only because it has become such a platitude. An obvious starting point would be to contest the key conviction of the modernist pedagogical canon, i.e. that teaching programs should be (to quote De Duve again) “based on the reduction of practice to the fundamental elements of a syntax immanent to the medium.” The lingering notion here is that the systematic exploration of elemental principles (shape, colour, texture, contrast, pattern, etc.) via practical exercises can be usefully applied to any medium.

Starting from scratch, would our virgin curriculum, founded on the CONTEMPORARY paradigm circumscribed above by such as Findeli, De Duve and Eno, logically manifest itself in the same way? If the boundaries between disciplines no longer hold, and with attitude, practice and deconstruction as the bedrock of our milieu, we surely need to rethink the nature of the primary tools and skills offered to new students. As trite as it might sound, “thinking” is both a tool and a skill—a big-C Cultural version of common sense as opposed to received wisdom:

If the question of art is no longer one of producing or reproducing a certain kind of object (and if the medium no longer sets the terms of making—what “painting” demands, or sets out as a problem) then a responsible, medium-based training, which always says how to make, can’t get to the question of what to make. How does one get from assign-ments that can be fulfilled—colour charts, a litho stone that doesn’t fill in after x-number of prints, a weld that holds—to something that one can claim as an artist, to something that hasn’t been assigned?

So there is a kind of gap or aporia that comes either in the middle of undergraduate art school or in between BFA and MFA, and that aporia marks a shift from the technical and teaching on the side of the teacher, to the psychological and teaching on the side of the student—working on the student rather than teaching him or her something. “He is saying this to me but what does he want?” as Lacan imagines the scene; or in the figure of the gift, “Is this what you want?” “Will you acknowledge this?” (Singerman, email 2006)

From this vantage, the idea of focusing on a more transferable “design thinking” implies not only easy communication and movement between disciplines (both physically and bureaucratically), but also integration with the broader social sciences (philosophy, sociology, cultural studies) in view of what Potter described earlier as knowing “the present as a commitment in depth.”

Further, it seems imperative to introduce such “design thinking” at the very beginning of an undergraduate program, precisely to allow a more sophisticated understanding of culture and Culture to inform and infect subsequent practical work. Such a model could be implemented in different ways, at different extremes. One would be to offer a course in “design thinking” prior to any other media-specific and/or practical teaching; another would be to run it alongside other teaching, as a regular counterpoint to orthodox practical classes; a third would be to make it the focus of an entire department, with specialisms, workshops and other practical teaching available as supplementary offshoots.

Such a class, course, or even department might effectively begin with an open discussion about the very nature of working as a contemporary artist/designer—which immediately implies interrogating this very duality. Again, all this leans towards the development of prioritizing a general thinking about the field and its surround, rather than making in a specific medium. We could consider it the nurturing of a critical faculty as a formative skill.

Artists are the subject of graduate school; they are both who and what is taught. In grammar school, to continue this play of subjects and objects, teachers teach art; in my undergraduate college, artists taught art. In the graduate school artists teach artists. Artists are both the subject of the graduate art department and its goal. The art historian Howard Risatti, who has written often on the difficulties of training contemporary artists, argued not long ago that “at the very heart of the problem of educating the artist lies the difficulty of defining what it means to be an artist today.” The “problem” is not a practical one; the meaning of an artist cannot be solved by faculty or administration, although across this book a number of professors and administrators try. Rather, the problem of definition is at the heart of the artist’s education because it is the formative and defining problem of recent art. Artists are made by troubling it over, by taking it seriously. (Singerman, 2001)

Finally, for now: what’s the potential payoff of an art/design pedagogy founded on this “critical faculty”?

A provisional answer: to educate students primarily towards becoming informed thinkers, sensitive to both culture at large (“the world”) as well as their specific Culture interests (“the art world,” “the design world”), and how they overlap and effect each other …

… by introducing a vocabulary geared towards describing both forms of c/Culture (for example, defining and debating the intricacies of the terms in De Duve’s table, from “talent” to “deconstruction”) …

… in order to develop the foundational skill of coherent articulation—the ability to explain, justify, defend, criticize, and argue …

… towards a level of critical sophistication in which “critical” refers to engaged discussion as part of a historical and theoretical continuum rather than the usual rudimentary value judgments of the group or individual crit …

In short, to foster a climate of progressive reflexivity.

Educating reflexivity—teaching students to observe their practice from both inside and outside—fosters the ability to anticipate potential roles and their effects, so that upon entering the field, industry, market, academia, or whatever other facet of the after-school environment, they should at least be equipped to ask whether they

want to / ought to / refuse to

enter into / challenge / reject the

existing art & design field / industry / market / academia

Alain Findeli proposes a similar model (expressed in terms of teaching an “intelligence of the invisible” through “basic design”) in order to redirect design education from its current path towards “a branch of product development, marketing communication, and technological fetishism.” “If it is not to remain a reactive attitude,” he says, “it will have to become proactive …”

If we accept the fact that the canonical, linear, causal, and instrumental model is no longer adequate to describe the complexity of the design process, we are invited to adopt a new model whose theoretical framework is inspired by systems science, complexity theory, and practical philosophy. In the new model, instead of science and technology, I would prefer perception and action, the first term referring to the concept of visual intelligence, and the second indicating that a technological act always is a moral act. As for the reflective relationship between perception and action, I consider it governed not by deductive logics, but by a logic based on aesthetics.

I believe that visual intelligence, ethical sensibility and aesthetic intuition can be developed and strengthened through some kind of basic design education. However, instead of having this basic design taught in the first year as a preliminary course, as in the Bauhaus tradition, it would be taught in parallel with studio work through the entire course of study, from the first to last year. Moholy-Nagy used to say that design was not a profession, but an attitude.

Didn’t he claim that this course was perfectly fitted

for any professional curriculum, i.e., not only for designers, but also for lawyers, doctors, teachers, etc.? (Findeli, 2001)

This is not too far away from the recent “MFA is the new MBA” soundbite, which asserts another paradigm shift—namely, the business world’s recognition of the value of unorthodox thinking over traditionally conservative managerial procedures.

...

If all this were accepted, the immediate concern would likely be how to monitor and accredit such a curriculum—not to mention how to articulate and justify it to apprehensive parents, and their children who are seemingly becoming more parent-like than their parents in their hunger for the pacifying fiction of predictable pathways to employment. But this is jumping too far ahead: I want to end, or begin, by emphasizing that what should be done? ought to take clear precedence over concerns over how should we do it?

This is nothing more than sturdy “design thinking” itself, of course—but that doesn’t diminish its urgency. If such a reflexive review doesn’t happen soon, the usual brand of opinion-polled, market-driven decision-making will surely end up destroying the industry it floods with its supposedly satisfied customers—if nothing else, by making it unbearably bland. I suspect that maintaining this simple what-then-how sequence may well be the most difficult part.

*

References:

In the hope of helping the text flow a bit better I decided not to foot- or endnote the many books and articles cited in the texts, but all the relevant references are finally collected here. Also, to make this “reader” a little easier to read I took the dubious liberty of slightly amending many of its embedded texts. Please note, though, that I avoided marking omissions with a “[…]” so as not to end up with a completely dotty text. Naturally I was careful avoid any loss or distortion of meaning, but still strongly refer the reader back to the primary sources.

Bridgman, Roger, “Statement” / “Who Cares,” Dot Dot Dot, no. X (2005)

Calvino, Italo, Six Memos for the Next Millennium (London: Jonathan Cape, 1992)

Conlin, Michelle, “Champions of Innovation,” Business Week, June 8 (200)

De Duve, Thierry, “When Form Has Become Attitude—and beyond” in Theory in Contemporary Art sSince 1885 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005)

Eno, Brian, A Year (With Swollen Appendices) (London: Faber & Faber, 1996)

Findeli, Alain, “Rethinking design education for the 21st century: theoretical, methodological and ethical discussion,” Design Issues, vol. 17, no. 1 (2001)

Kinross, Robin, ed., Anthony Froshaug: Documents of a Life / Typography & Texts (London: Hyphen, 2000)

Pirsig, Robert M., Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (New York: William Morrow, 1974)

Potter, Norman, What Is a Designer, 2nd ed. (London: Hyphen, 1980)

Seago, Alex, Burning the Box of Beautiful Things: The Development of a Postmodern Sensibility (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995)

Singerman, Howard, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999)

Singerman, Howard, email to Frances Stark reproduced in the Introduction to Frances Stark, ed., Primer: On the Future of Art School (Los Angeles: USC, 2007)

Van der Velden, Daniel, “Search and Destroy,” Metropolis M, no. 2 (2006)

Whitford, Frank, Bauhaus (London: Thames & Hudson, 1984)

Wigley, Mark, Untitled contribution to the “Education” issue of AD Magazine (Winter 2006)