Science, Fiction

2008

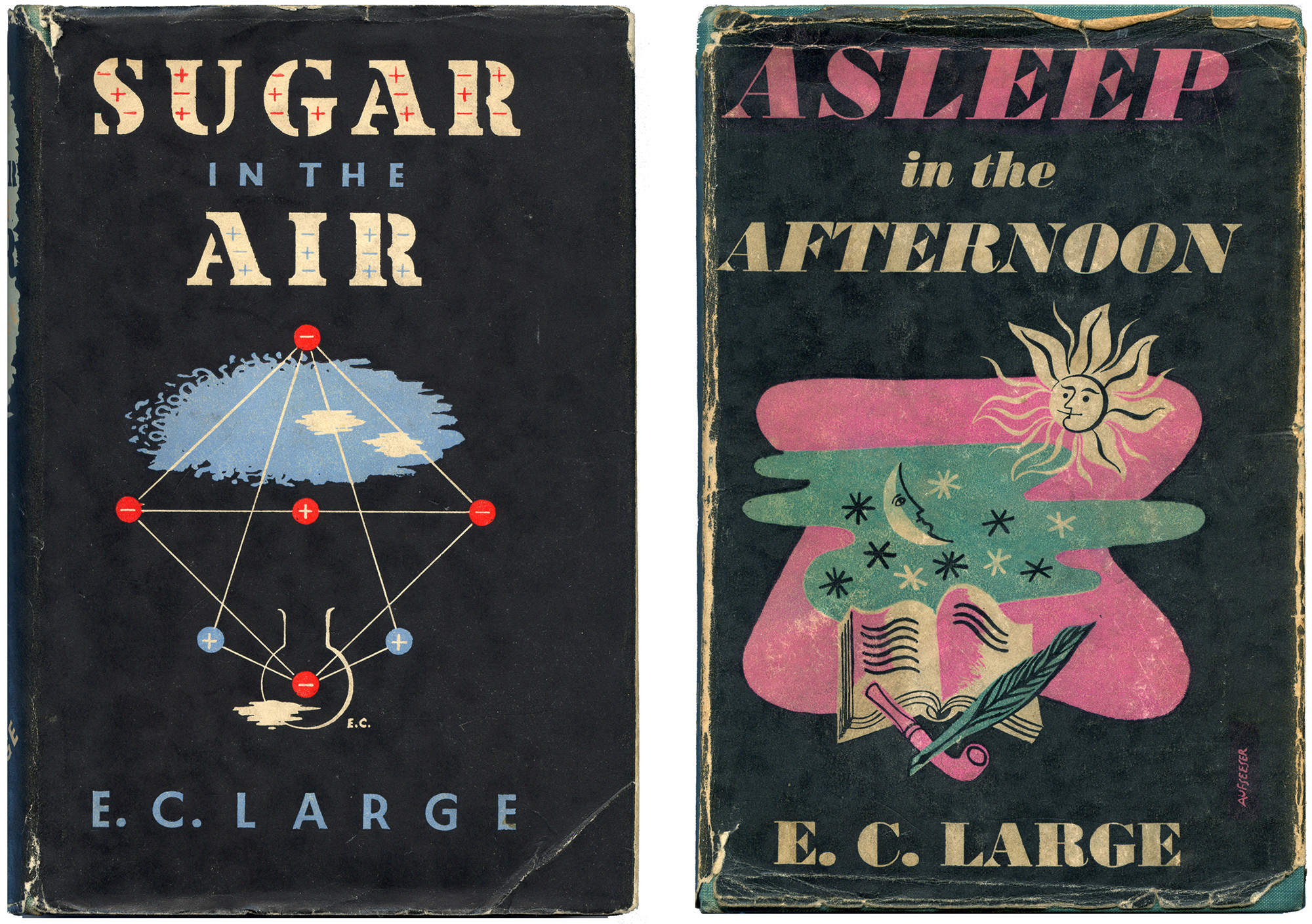

This essay on the work of mid-20th century author E.C. Large (1902–76), and in particular his first two related novels Sugar in the Air (1937) and Asleep in the Afternoon (1938), was written for a book of his essays and other short-form writing I edited together with Robin Kinross, God’s Amateur, which was published alongside reissues of the novels by Hyphen Press in 2008 (see also this accompanying interview). Around the same time a version of the essay also appeared in Dot Dot Dot 17 (2008).

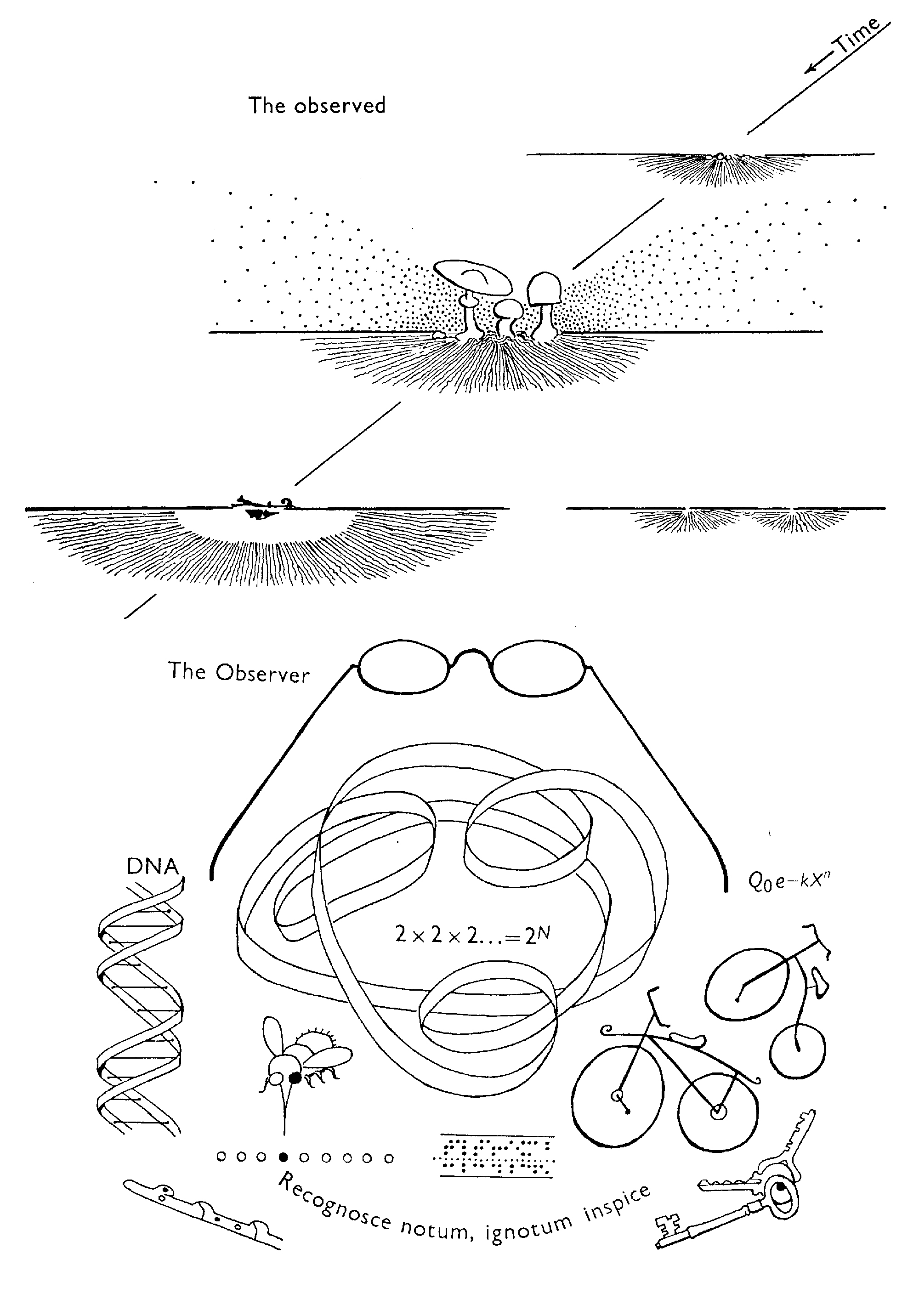

Lead image: Illustration by E.C. Large.

*

Scientific Method:

1. Define the question

2. Gather information and resources

3. Form hypothesis

4. Perform experiment and collect data

5. Analyse data

6. Interpret data and draw conclusions that serve as a starting point for new hypotheses

7. Publish results

…

Ideally this essay will be written with deceptive ease—or at least something akin to the casual dedication in Large’s second novel:

To E.H. over a bottle of wine

In other words, it should embody the steady spirit of its subject, a writer who was always chasing the underlying, irreducible truth of each new situation. Both E.C. Large and his fictional double C.R. Pry are driven (not to say condemned) by the need to seek out the root causes of local defects—“what exactly is going on here?”—and the shortcomings that need to be exposed are usually social ones. Such self-discipline is manifest in Large’s ragged hand- and typewritten manuscripts, the understated precision and protracted pace of which are already lost to another generation. They are fossils of a practical decorum which has been abandoned, perhaps irretrievably, along with the wider implications of civility beyond language, by which I suppose I simply mean “good manners.” They also convey a distinct sense of practice; that is, plainly practising writing to get better at it rather than some grander calling to the practice of writing—and in Large’s case the proletarian overtones of “writer” resonate more convincingly than the pretensions of “author,” as he implies himself:

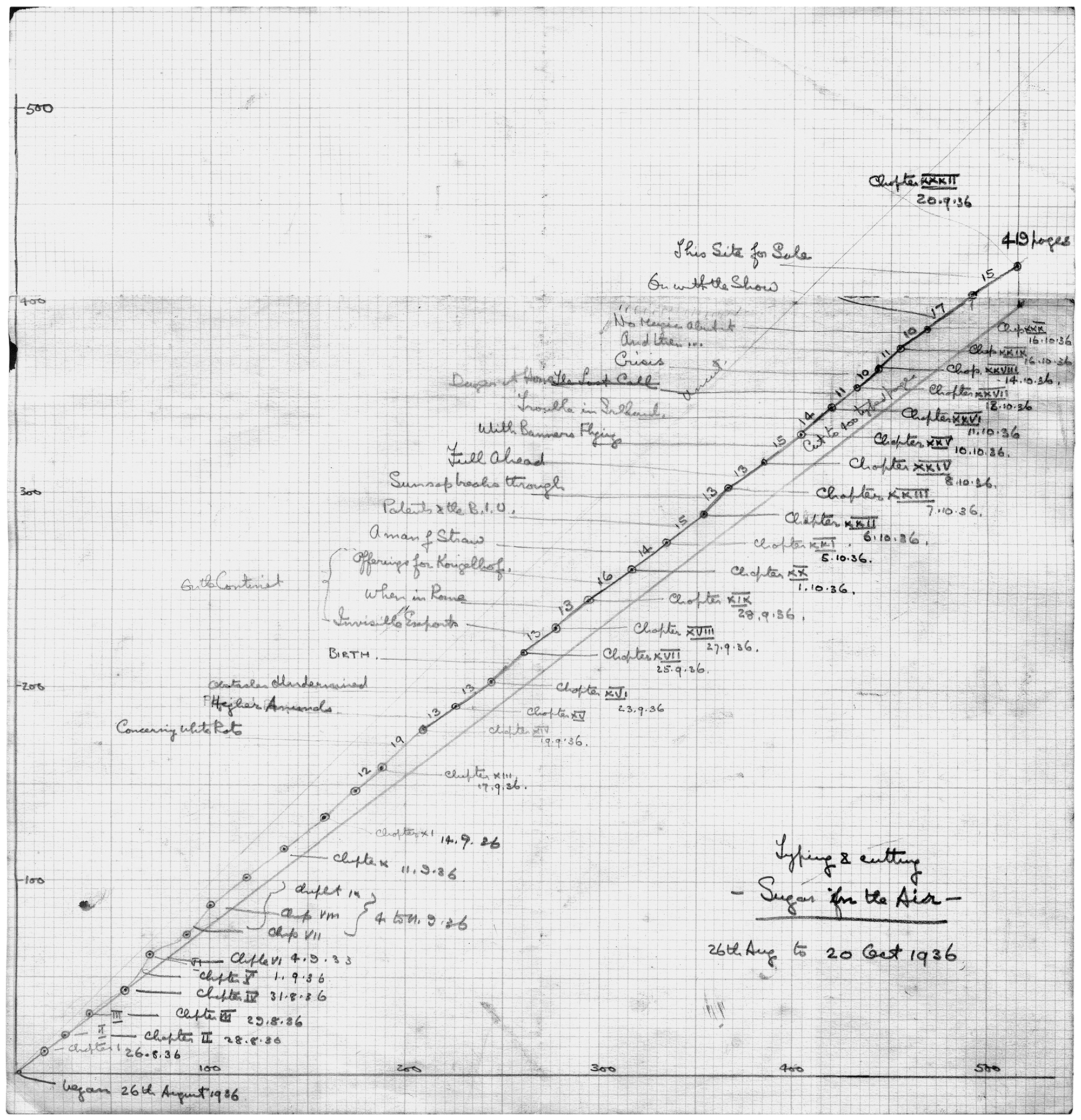

He set out the typewriter, the manuscript, the paper and his several mechanical aids to production, on his table, as though he were going to be timed for typewriting under the Bedaux system, but he did not yet start. Forty days and forty nights! Five hundred and sixty-one pages in that stack of manuscript four inches high … Even so, the typescript-production graph had still to be prepared. On this graph pages of typescript were to be plotted against the pages of manuscript. An ideal line on the graph showed how many pages of typescript there should be when he had reached any given page of the manuscript, if he was going to end up with exactly four hundred typed pages …

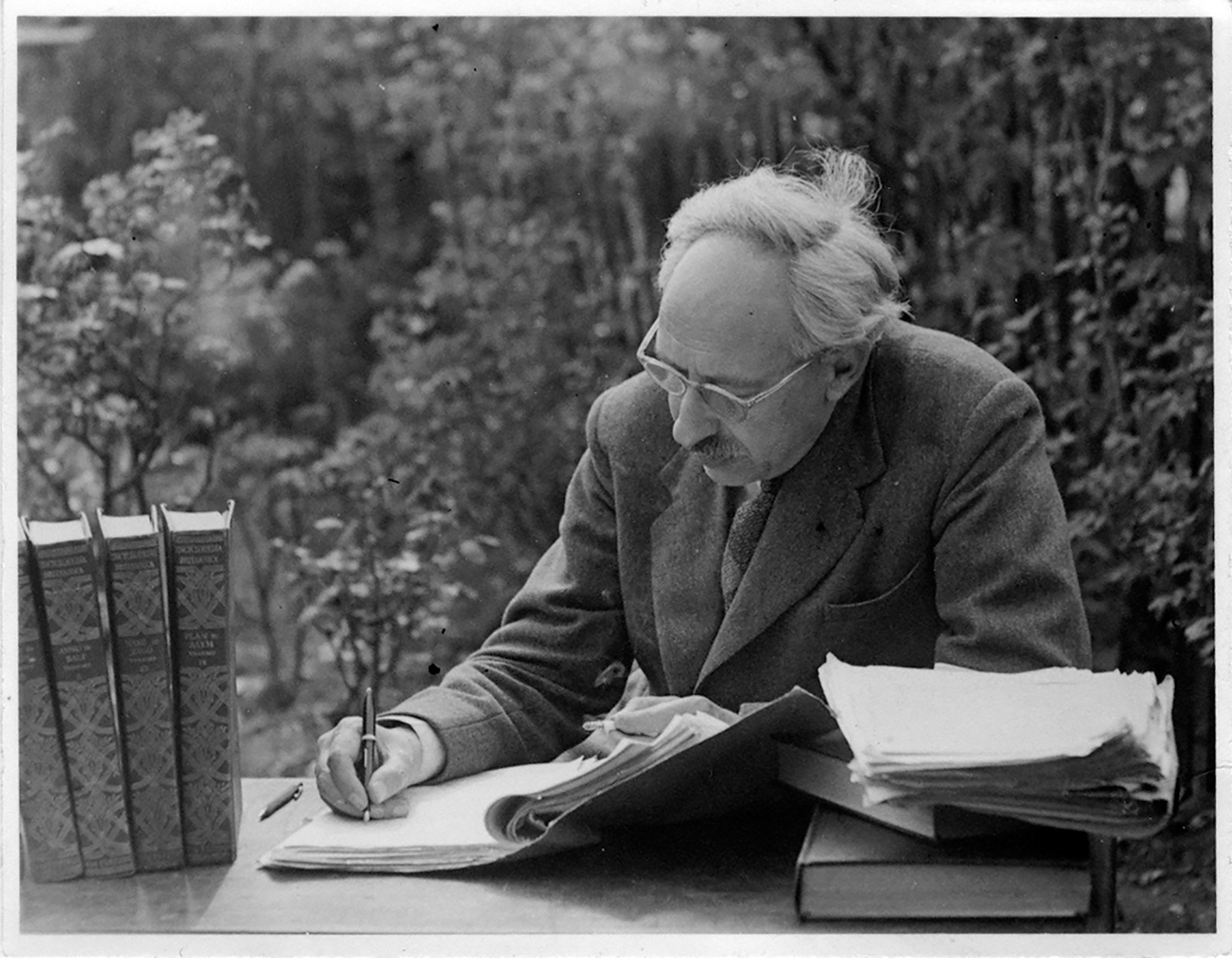

My copy of Large’s fourth and final book Dawn in Andromeda arrived in the mail with an auspicious photograph glued to the inside of its cover: the writer apparently at work on the manuscript of the same book, sat behind a makeshift table at the end of a garden with a pile of what appear to be encyclopaedias or dictionaries. According to an obituary note the picture was probably taken on a Sunday morning, and this casual snapshot of the weekend writer implies two ideas which are not necessarily contradictory—that for Large writing was a pleasant pastime, but also one urgent enough to occupy what was then still upheld as a traditional (i.e.religious) day of leisure. This is not lower-case work in the sense of labour, but capitalised Work in the sense of artistry; a necessary hobby, then, with as much allusion to compulsion, of being held in a grip, as to the fix of creation. The personal and communal dilemmas that arise from this conflict form the basis of Large’s first two novels, Sugar in the Air and Asleep in the Afternoon, and given their largely autobiographical content it is clear that Large simply—constitutionally—had to write. This urgency, which only occasionally slides into desperation, is at the root of both novels’ recurring motif: the struggle to “win back” time from industry, the staking of a claim to live life rather than spend it occupied by the drudgery of labour, manual or otherwise. The elliptical fact that for Large this “living” was practically synonymous with “writing” (at least at the time these first books were written, as well as during the timeframe within the novels) is typical of the looping self-reflexivity that propels it.

Double Bind

Sugar in the Air is a story of the cycle of an idea. In this case the biological one compressed into its deadpan title—a novel’s “only line of poetry” according to Large (speaking in character). Charles Pry is a chemical engineer fast approaching the end of two years’ self-imposed unemployment spent trying to write, who unwittingly finds himself directing an improbable attempt to produce glucose from carbon dioxide. To the surprise of all involved, not least himself, Pry’s experiments succeed. He establishes a commercially viable factory, then involves himself in all aspects of its production, incrementally establishing the soundness and success of its product Sunsap, which is eventually processed into useful cattle feed. Pry then continues to manage the company long enough to observe—with public detachment and private dismay—its hapless board of directors dismantle the entire project. The decline is as rapid and reckless as its progress was slow and careful, a domino effect of conflicting vested interests in which the frequently infantile logic of industrial capitalism come across as both easily avoidable and depressingly inevitable. By the close of the novel both Pry’s factory and his ambition have shut down, and he is precisely back where he began, having secured enough profit from the venture to support himself without work for a further couple of years.

Had Large stopped there he would have left a debut whose first impression as a rudimentary portrait of inter-war industrial relations reveals itself on closer inspection to be more concerned with scrutinizing the human ones underneath. Large carefully inscribed a double layer into the novel through a cast of caricatures (mad scientist, tyrannical director, jealous colleague, etc., with Pry playing the human being) who are at once too blatantly clichéd to come across as mere realism, and too vividly drawn from life to come across as mere parody. Sugar in the Air’s default temper is sardonic and satirical, but both Large and Pry, author and protagonist, care too much despite themselves to come across as one-dimensionally bitter. Pry is more complex a character than the so-called angry young men who would soon populate postwar English fiction, being essentially an articulation of inward deliberation rather than outward bravado, marked by the constant struggle to identify, understand and come to terms with his own fundamentally contradictory impulses. This self-doubt is the core of Large’s writing (“at its best in its helplessness,” as he once reflected) and tragicomically manifest in the gap between his straightforward no-nonsense depiction of the anything-but-straightforward nonsense of human relations.

By similar oppositional design, Large painted his social backdrop deliberately larger than life, so conspicuously “of its time” that the novel’s more timeless aspects—its attitudes—are offset in greater relief. In other words, the false scenery is patently detachable (therefore transposable) and such technical doublethink is both central to the novel’s effect and one of its key themes. Picking at the details of what Pry christens “nominal democracy”—everything done in the name of something else—Large repeatedly attempts to reach beyond this surface to essence. In fact, this extract from one of his shorter journal pieces might easily double as blurb for Sugar in the Air’s dust jacket:

About Socialism, about Communism, Pacifism, Capitalism, yes, but something more than the mere reshuffling of the jargon of Socialist theory. The tags used, because for some they are terms of reference, but the search always into the contents of these parcels, not the tags.[1]

These contents are his characters’ beliefs, conceits and motivations; ways of thinking articulated at the level of everyday interactions, not yet hardened enough to qualify as bona fide (theoretical, polemical) philosophies, and so more practicable: easy to relate, and to relate to. But Large didn’t stop there; instead he wrote a sequel, or a meta-sequel. Hardly pausing for breath and barely bothering to re-introduce the cast, Asleep in the Afternoon picks up exactly where Sugar in the air left off, then proceeds to continue, duplicate, and mirror it all at once. As such, the sequel is also about the cycle of an idea, only this time a literary rather than scientific one. Instead of managing a factory, Pry writes a novel—also called Asleep in the Afternoon—whose own progress is related through various summaries, paraphrases or entire chapters embedded in the outer story. Asleep in the Afternoon quickly bifurcates into two stories, with Pry’s “real” experiences increasingly informing those of his characters—and ultimately, of course, a third once the reader realizes that Pry’s writing Asleep in the Afternoon is itself a more or less biographical account of Large’s writing Sugar in the Air.

Setting into motion another snake-eating-its-own-tail, Large concludes his second novel with Pry’s first being published and acclaimed, along with enough advance royalties and promise of a literary career to avoid the permanent threat of a “return to industry.” Both books follow an identical looping trajectory from a state of mental and physical inertia, through a period of passion, activity and enlightenment, then back to the former state, a sense of resignation and only the merest glimmer of satisfaction at having “used” the time creatively. The books themselves—both fictional and actual—are now monuments to this oasis of economic “freedom,” two years frozen in abstract form of text-as-thought and physical form of book-as-object.

It is a platitude that debut novels frequently involve protagonists who are thinly-veiled versions of their authors, and one good reason for avoiding re-presentation of Large through narrative biography here is because the essential aspects of both stories are based on Large’s own life, with little attempt to disguise it. Like Pry, Large worked as a chemical engineer (making Sulsol rather than Sunsap) before being able to support himself briefly as a writer, and likewise found himself at the end of both books faced with the tenuous promise of a literary career conditional on adequate sales.

Low Modernism

My wish here is to insist that Sugar in the Air and Asleep in the Afternoon ought to be considered a single piece of work. To ignore one or the other is to miss much more than half the story, the depth of Large’s art and the breadth of his work’s inherent ambition.

With the slightest hint of derision Large opens Sugar in the Air with Pry “trying to write a book, a treatise,” an introductory glimpse of the self-awareness that will intermittently descend into self-loathing. Here Large reflects his context not only by describing his surroundings, but by practising and—crucially—observing the practice of practising the self-consciousness typical of modernist literature of the surrounding decades. For years I’ve claimed that one reason for republishing Large is that his reflexivity was ahead of its time, but on reflection this claim doesn’t actually hold up too well considering the lineage of involuted fiction that predates it. This stems from Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (arguably further back to Rabelais or even Cervantes) then on to Joyce and Beckett, their German-writing contemporaries such as Musil and Walser, and later stretching on to writers as diverse Borges, Nabokov and Calvino. This branch of literary modernism ran roughly parallel to the “heroic” phase of twentieth century art and architecture, similarly liberated by formal experiment and the exposure of underlying mechanics. Its proponents worked towards a literature founded on progressive realism (more simply—and problematically—under the banner of “truth”) as opposed to the supposedly stagnant presence of the bourgeois Romantic narrative.

The quality that sets Large’s writing apart from these broad contemporaries, however, is essentially anti-literary: his novels (particularly) are grounded. While technically sophisticated, they don’t seem to be. While the writing is consistently austere it remains generous, buoyed against its regular pockets of claustrophobia and desperation by a solemn kind of joy and stubborn, if still half-ashamed, independence. Take Pry’s autobiographical vignette, delivered here to Sunsap’s board of directors, who regard him almost fondly as an eccentric irritant:

“If you will consult your records you will find how long I have been with this company. Before that I was technical manager of a breakfast food company in Durham. My initials are C.R., I enjoy good health, I am punctual and industrious, and of temperate habits. I have no morals, no principles and no politics.”

Next to the show-offishness of the modernist canon (Joyce as stylistic virtuoso, Beckett as minimal extremist, Borges as vertiginous fantasist, Nabokov as shadow puppeteer, etc.) Large’s debut novels are, then, unassuming. The tone, manner and trajectory of Large’s narration is straight-faced, precise and plodding—qualities which might amount to a dour “scientific” demeanour if not so regularly checked by self-deprecation and a tendency to daydream. In fact, Large writes with such alacrity that his approach might more accurately be considered “low” in relation to the more cerebral, propulsive “high” modernists, and suggests why his reputation fell quickly below the critical radar. Large shares something of the stereotypical British modesty and resolute smallness of such as G.K.Chesterton (astute observation and local pragmatism) or Henry Green (the mores of particular social pockets), but Sugar in the Air and Asleep in the Afternoon fall most comfortably in line with Robert Tressell’s socialist tract-novel The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists (1914), whose righteous everyman Frank Owen might be considered a blueprint of Pry in an age before irony, only a quarter of a century earlier.

While in retrospect Large’s directness might be considered an alternative to—or relief from—the asceticism of higher-brow Continental modernism, the British critics of 1938 found Asleep in the Afternoon’s cleverness reprehensible, another characteristically British attitude which has since dogged a strain of self-reflexive British writers such as B.S. Johnson and Alasdair Gray. Johnson’s Albert Angelo (1964) was the first of a sequence of what he called autobiographical novels, founded on the staunch precept that “telling stories is telling lies” and whose narrative accordingly breaks down into an “almighty apotheosis” of stark self-reflection. Although critical reception to Johnson’s work was uneven (but by no means predominantly negative) to Johnson’s mind he was always pejoratively labelled “experimental,” a term he came to categorically reject. Gray’s compulsive Glaswegian odyssey Lanark (1981), on the other hand, employs baroque appendages of self-parody (notes, asides, appendices, and typographic play) which have been consistently read as a security device deliberately set to anticipate and defuse external criticism; a claim which grows increasingly vertiginous when some of the critics of this device also appear to have been invented by Gray himself.

The novels of Large, Johnson and Gray have little in common, either stylistically or thematically, yet it seems to me they have all ostensibly arrived at a similar point of artistic involution through serious, candid self-reflection. Their mutual commitment to an idea(l) of honesty—and the various formal solutions it has contrived—is rooted in a shared attempt at literary transparency whose intentions and implications are both personal and social.

This distinctly local breed of involution defines another overlooked piece of British reflexivity: Lindsay Anderson’s feature film O Lucky Man! (1973) is a three-hour anti-epic which follows its cartoonish naive-idealist Michael Travis (played by Malcolm McDowell) around England, its scenes partly written in transit between shooting. In an extended closing sequence Travis, lost in an evening crowd at Oxford Circus, happens upon a sign—“TRY YOUR LUCK!”—and is directed into an open film audition populated by the rest of the cast of the same film the viewer is just about to finish watching, as well as Anderson the director playing himself in charge of its casting. When Travis is pulled from the crowd for a screen test, Anderson closes in and repeatedly asks him to smile for the camera. He refuses a number of times, then—in an apparent epiphany—his confused, indignant frown starts to reverse and the camera cuts. The film effectively ends on this ambiguity I have since come to interpret as: only laughter could steel him in his new awareness.

Just as the art of Pry reflects the life of Large, and vice versa, this scene mirrors Malcolm McDowell’s first actual audition for the director, which resulted in their earlier collaboration If… (to which O Lucky Man! can reasonably be considered a sequel). Anderson also worked in the same reflexive territory as a number of continental European counterparts, most obviously the French New Wave, yet—again like Large—departs from them where the work-turning-in-on-itself seems less the knowing gesture of an intellectual auteur invested in the history of cinema, and more an intuitive solution to a “technical” problem encountered during the writing: how to offset a layer of meaning—the politics of transparency—drawn from the subject rather than applied to it.

During my most recent re-reading of Large’s novels, I had the uncomfortable feeling that my attraction to all this arch self-awareness of such as Large’s art was merely a matter of taste (like preferring red to green). This bothered me inasmuch as I had previously assumed the self-reflexivity carried some kind of critical, moral or ethical weight—a conviction which seemed suddenly groundless, or at best too oblique to be philosophically practicable. The more I considered it, the less I was able to hold the idea in focus, and it was some time before the itch was scratched by another anecdote to another introduction to another classic work of involution, the extensively annotated version of Nabokov’s Lolita, as compiled by Alfred Appel, Jr., worth quoting at length here:

One afternoon my wife and I built a puppet theatre. After propping the theatre on the top edge of the living room couch, I crouched down behind it and began manipulating the two hand puppets in the stage above me. The couch and the theatre’s scenery provided good cover, enabling me to peer over the edge and watch the children immediately become engrossed in the show, and then virtually mesmerized by my improvised little story that ended with a patient father spanking an impossible child. But the puppeteer, carried away by his story’s violent climax, knocked over the entire theatre, which clattered onto the floor, collapsing in a heap of cardboard, wood and cloth—leaving me crouched, peeking out at the room, my head now visible over the couch’s rim, my puppeted hands, with their naked wrists, poised in mid-air. For several moments my children remained in their open-mouthed trance, still in the story, staring at the space where the theatre had been, not seeing me at all. Then they did the kind of double-take that a comedian might take a lifetime to perfect, and began to laugh uncontrollably, in a way I had never seen before—and not so much at my clumsiness, which was nothing new, but rather at those moments of total involvement in a non-existent world, and at what its collapse implied to them about the authenticity of the larger world, and about their daily efforts to order it and their own fabricated illusions. They were laughing, too, over their sense of what the vigorous performance had meant to me; but they saw how easily they could be tricked and their trust belied, and the shrillness of their laughter finally suggested that they recognized the frightening implications of what had happened, and that only laughter could steel them in their new awareness.[2]

Experience and Convenience

Reflection might be Large’s (Pry’s) defining quality, but his self-criticism is rarely wasted. Rather than wallow in his insight he uses it, as one critic noted: “Mr Pry was quite a man, though I don’t recall the author’s saying so … He is no hero but he gets things done.” Pry’s rite of passage through Sugar in the Air is mirrored in a recurring conversation with his appointed mentor, Professor Zaareb, who repeatedly chastises his occasional egoistic preoccupations with short term success (generally comic lapses into vanity, materiality, or delusions of grandeur). Zaareb’s mature, if not exactly Zen, priorities are, by comparison, always “for science’, which is to say broad cultural progress and collective enlightenment rather than immediate local benefit and personal gain.

“You young men never see that Research is a cultural pursuit: you wouldn’t expect Big Business to pay you for writing poems or having music lessons, would you?”

At the beginning of their working relationship Pry interprets Zaareb’s attitude as plain arrogance, but when he hesitates during the patenting—the public dispersion—of their research and Zaareb demands:

“You pretend to want to give your work to the world, don’t you? Now that you are forced to do so, what cause have you to complain?”

A humbled Pry replies:

“I am beginning to feel, Dr. Zaareb, that my real reward in all this is the privilege of association with people like you.”

This exchange marks the end of Pry’s professional adolescence—in part through the new realization that Zaareb’s disinterest is a safety valve against hubris. And if this new realization of his work as a social rather than a personal project destroys some of its intense appeal (or “love’), the same detachment insulates him against the destructive actions of the board of capitalists. As they plough through one slapstick decision after another, systematically unravelling the immediate practical results of Pry’s two years’ labor, his wider contribution to scientific knowledge remains immune.

Large’s push towards a form of literary transparency can be read as a form of personal (and, crucially, personally-arrived-at) resistance to prevailing forms of government and other social management. That its righteous independence seems so pertinent 70 years on is a reflection of how the “nominal democracy” Pry solemly regards has only gained momentum since, towards a critical mass now defined (in modern Western society at least) by ubiquitous spin doctoring, the widespread distrust of government, and the resultant gulf between any state and the public it contrives to represent. In short, a collective resignation to the failure of democracy, or at (the very) least to lingering socialist notions of it.

At the turn of the century in his survey of The Nineties (2001) the cultural critic Michael Bracewell portrayed immediate history as a total inversion of Large’s ideals. Contrary to Large’s 1930s drive to get “beyond surface to essence,” Bracewell’s 1990s stall at the subtitle: When Surface was Depth. In this scenario culture has been reduced to a number of familiar codes: infantilism, chauvinism, retroactive reference, and militantly manufactured “authenticity”—all packaged through a “comedy of recognition,” contained by ubiquitous quotation marks at least a step removed from any founding “reality.” This is the logical, tragic outcome of Large’s “nominal democracy,” with experience supplanted in the name of something else: convenience.

“The end result of these ideas,” Bracewell concludes, “would be the feeling that, we, the consumer democracy, were in fact post-political—and afflicted with a Fear of Subjectivity.” The germ of this condition was already permeating Asleep in the Afternoon some 60 years earlier—in the following passage, for example, where Pry gently mocks the “convenience” of the book club which recommends his own novel as “book of the month”:

Wonderful! No routing about in second-hand book shops; no venturing and searching for themselves; no counting the money in their pockets before plunging on a book they had slowly come to desire. No carrying the coveted book home, under their coat, hiding it from Mary or saying it cost rather less than it did, half ashamed of the extravagance, when it could have been read for nothing, sooner or later, at the British Museum. No looking over their shelves and seeing how their taste and understanding had grown with the years. No sense that the choice of books was like the choice of friends. Perhaps they had their friends, and maybe also their concubines, chosen for them by a selection committee. What a lot of trouble it saved.

Large repeatedly draws attention to this loss of experience in the face of convenience, and invokes the corollary “convenience” of hollow political rhetoric versus the “experience” of quantifiable and verifiable facts. His own prose is accordingly artless, stripped of affectation, its voice a familiar, even-tempered common denominator. The usually reticent Pry even finds himself heckling a speaker on the subject in Asleep in the Afternoon:

“The contradiction to which the bourgeois speaker draws attention is dialectical and inevitable under capitalism.” There was a murmur of approval; the meeting seemed to find this answer completely satisfactory. “That is so much cant,” said Pry, “and one useful way of preserving culture is to speak plain English.”

Pry’s call for common language here is supported by Large’s example, writing the scene specifically and economically himself, casting out “about half the present vocabulary of politicians, clerics, philosophers, economists and others afflicted with proselytising zeal’. In a contemporaneous book review (of The Tyranny of Words) for the New English Weekly he promotes such “semantic discipline” by trawling various examples of overblown rhetoric and censoring each redundant word with a pragmatic “blab” to emphasize the point.[3]

Classic Romantic

Large’s writing is rife with multiple meanings, carefully crafted for the close reader whose assumed absence is but one aspect of his artistic melancholy: “two or three people in a thousand would taste it, and it would warm the cockles of their crapulous hearts” acknowledges Pry with a kind of bitter, self-preserving glee when “explaining” the poetry of Asleep in the Afternoon’s title to Mary. “All the rest might think it wholly sweet and delightful ….” Large’s chapter headings alone are rife with double and triple entendres, but the novels’ shared subtitle, A Romance, is more prominent and allusive than most for a number of reasons.

First, because the tone and stance of both books are consistently—romantically—against all odds, their very publication barely believed by Large himself as some miracle combination of trial, error, good fortune, and timing. Second, with regard to the fact that the definition of romance as “ardent emotional attachment or involvement between two people” could be rewritten as “… between a person and his work” to describe Large’s (Pry’s) professional temperament—or equally, “… between an author and his reader,” for that matter. Third, because of the constant sense of his trespassing on a foreign discipline, romantically spending (or wasting) time and effort on an activity without immediate or obvious gain, and most regularly justified to himself as a debt owed in lieu of time lost to prolonged study and forced labour. Fourth, with regard to that essential uselessness of writing which affords it ironic agency, manipulating the ills of marriage, industry, government, and religion into art—the romantic distillation of sugary life from dead air.

But above all because of the audacity with which Large slips his contrariness past the reader (on the title page!) by assuming the guise of conventional scene-characters-plot Romantic novels—which they are, in part; but they use rather than embody the form, and the distinction is critical. Sugar in the Air is a straightforward indictment of industrial capitalism and its attendant envy, greed and avarice, while Asleep in the Afternoon admonishes a public contentedly dormant on the eve of war. Ultimately, Pry (Large) is resigned to the deeper causes of both circumstances, and takes only the flimsiest, most suspicious comfort in the apparent dignity of his art as a personal stand (or coping device). Another critic portrayed him as being

so competent in his work and dedicated to it and personally decent, in short so expressive of the qualities we demand of any proper citizen, that he has no time or thought for self-advertising and thrusting and bald advancement and front, and is thus naturally put out like garbage in the end, the pure damn fool.[4]

As an overview of Large’s four published books, Sugar in the Air (1937) is a piece of fiction about science, Asleep in the Afternoon (1938) is fiction about the science of writing fiction, The Advance of the Fungi (1940) is a history of science with the tone of fiction, and Dawn in Andromeda (1957) is “pure” science fiction (which is to say that for the first time it adheres to the conventions of a genre—and is less inspired for doing so). Again, this cross-pollination of approaches, voices and genres from Large’s various careers seems to be rooted in Large’s autodidactic discipline, the constant flexing and toning of a literary muscle.

We leave Pry at the close of Asleep in the Afternoon, his “book of the month” a confirmed best-seller, considering a return to science and an adventure involving organic micro-cultures rather than London’s literary culture. Having dutifully trawled his own reviews with amusement and breezily observed the dismantling of his book’s window display, the folly of writing seems adequately drained from our anti-hero’s system—he is suddenly prepared for a profession instead of a romance. And so Pry’s circular existence starts over, once again mirroring Large’s actual circumstances. The poor commercial and critical reception of Asleep in the Afternoon appears to have extinguished the chance of his shorter non-fiction being published. In any case, the Second World War intervened, and Large’s next major undertaking—analysis of a national potato blight—was to “save his life”: agricultural research was acceptable war work for a sworn Pacifist.

While it seems that, professionally at least, Large never really reconciled the division of his scientific and literary work, it is precisely the symbiosis of the two that animates his early fiction today. His writing is defined by a wide-ranging set of interests, temperament and capacity which is equal parts classic and romantic—a duality which extends to any of the parallel dichotomies itemized by Robert M. Pirsig in his Zen and the Art of Motorcyle Maintenance: scientific vs. artistic, technical vs. human, or rational vs. emotional. Pirsig sets up these opposites in order to assert that the fundamental misunderstanding, disinformation, mistrust and hostility which characterizes modern societies are rooted in the personal and communal inability to reconcile these two poles:

Persons tend to think and feel exclusively in one mode or the other and in doing so tend to misunderstand and underestimate what the other mode is all about. But no one is willing to give up the truth as he sees it, and as far as I know, no one now living has any real reconciliation of these truths or modes. There is no point at which these visions of reality are unified.[5]

Like the small number of writers who have informed the present essay,[6] Large’s body of work is radical and instructive precisely because it covers all bases. His output ranges from the early reveries and reviews, through political commentary on topical issues (air raid shelters, conscription, propaganda), the domestic concerns of the family home and his “wind and wandering” travelogues, through to later papers on plant pathology. Whether “About the working class” or “The control of potato blight,” all are afforded the same serious consideration, dissected with impartial intellect, and the “findings” articulated through the bricks-and-mortar construction of pragmatic argument.

…

The careful ceremony of dismantling and reassembling the typewriter; the graphs which variously chart the novels’ progression and diminishing bank savings; the writer’s block, analysed, diagnosed, treated, and resolved within the space of a single chapter; and the vertiginous craft with which the wife’s knowing-her-husband-better-than-he-knows-himself is captured by necessarily knowing her a step better yet in order to portray it—all are vignettes drawn simultaneously from Large’s and Pry’s life and fiction which describe the unique disposition of the scientist-writer. Yet none are quite as succinct as his anticipation of the deft Möbius Strip of Asleep in the Afternoon’s design:

in a year I should pass through a rich variety of moods

∴ so would the book

∴ in that at least it would have some verisimilitude to life

*

Notes:

1. “Hail!,” in Stuart Bailey and Robin Kinross, eds., God’s Amateur: The Writing of E.C. Large (London: Hyphen, 2008), 44.

2. Alfred Appel, Jr., The Annotated Lolita [revised edition, 1991] (London: Penguin Books, 1995).

3. “The Semantic Discipline,” in Bailey and Kinross, God’s Amateur, 59.

4. Otis Ferguson, “One for the Reader” (review of Sugar in the Air), The New Republic, 8 September 1937: 139–40.

5. Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance [1974] (New York: Bantam Books, 1981), 62.

6. In particular, Large’s approach falls in line with most of the other writers published by Hyphen Press. There are brief, enigmatic allusions to Large’s novels in the books, notes and correspondence of Norman Potter and Anthony Froshaug, for example, that I like to imagine were deliberate acts of clue-planting for future close readers. Like Large, these writers work by simultaneous elucidation and example to articulate ideas which are the contents of the package represented by the label “modernism”; contents implied by this last excerpt from Sugar in the Air which refers to another fleeting critical spirit, the mercurial “Muller,” who—tellingly—disappears from the opening pages of the novel as soon as his point has been made:

When Muller quietly demonstrated that there are no “Laws” in nature, that “Facts” are only notions widely accepted, and that the subject matters of religion and philosophy are things more real than concrete and chrome steel, Pry was greatly shocked and surprised. When Muller went on to the subject of “Values” Pry found that those things which he had come to regard as his ideals were falling about his head in a litter of unimportance, and his whole attitude to “Life” stood revealed to him as trumpery, adolescent and mean. For this he blamed his social environment—until Muller went on to talk about “Environment.”