Procedural

2014

This extended caption to the image of the typescript was originally published on www.servinglibrary.org and in Bulletins of The Serving Library 8.

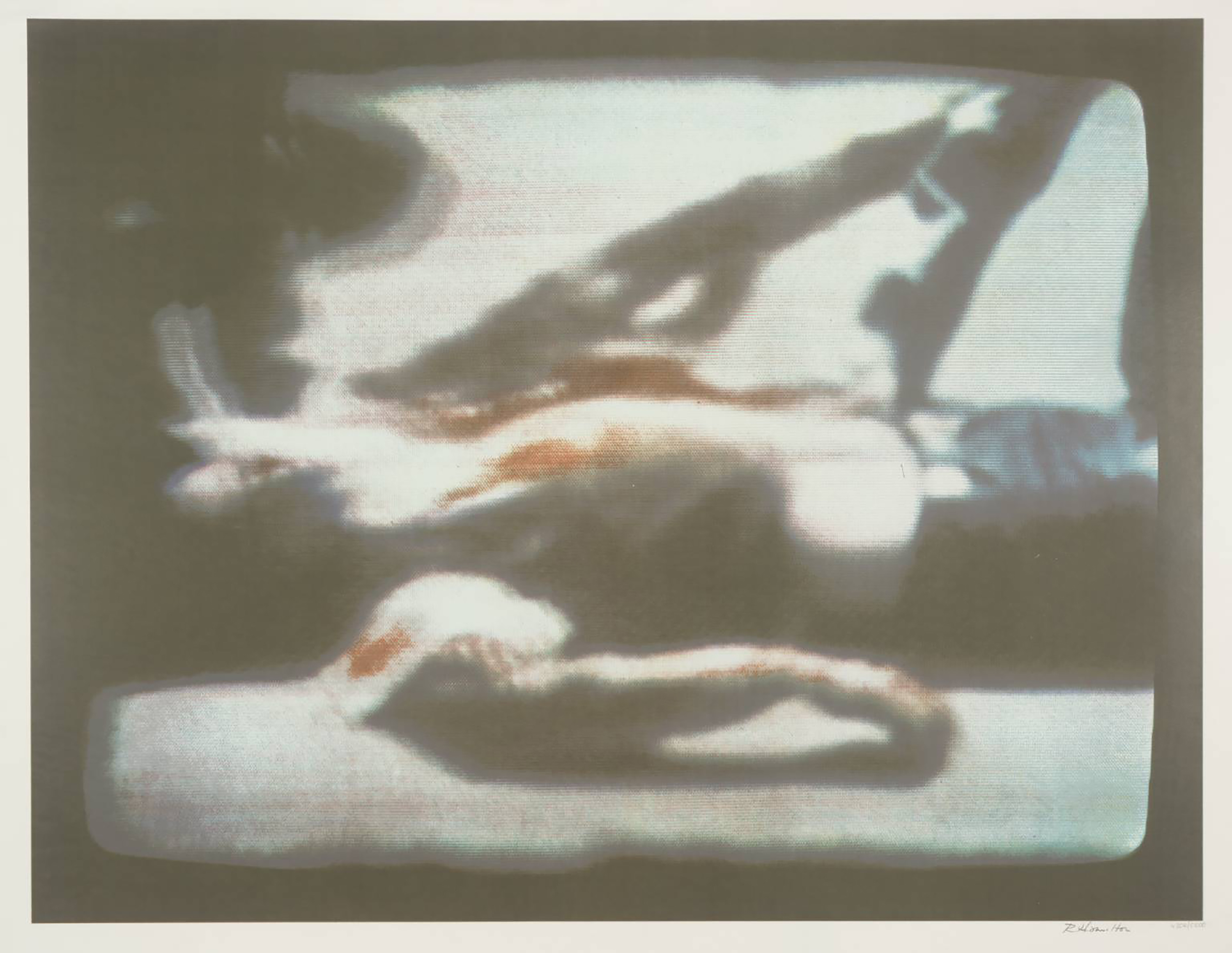

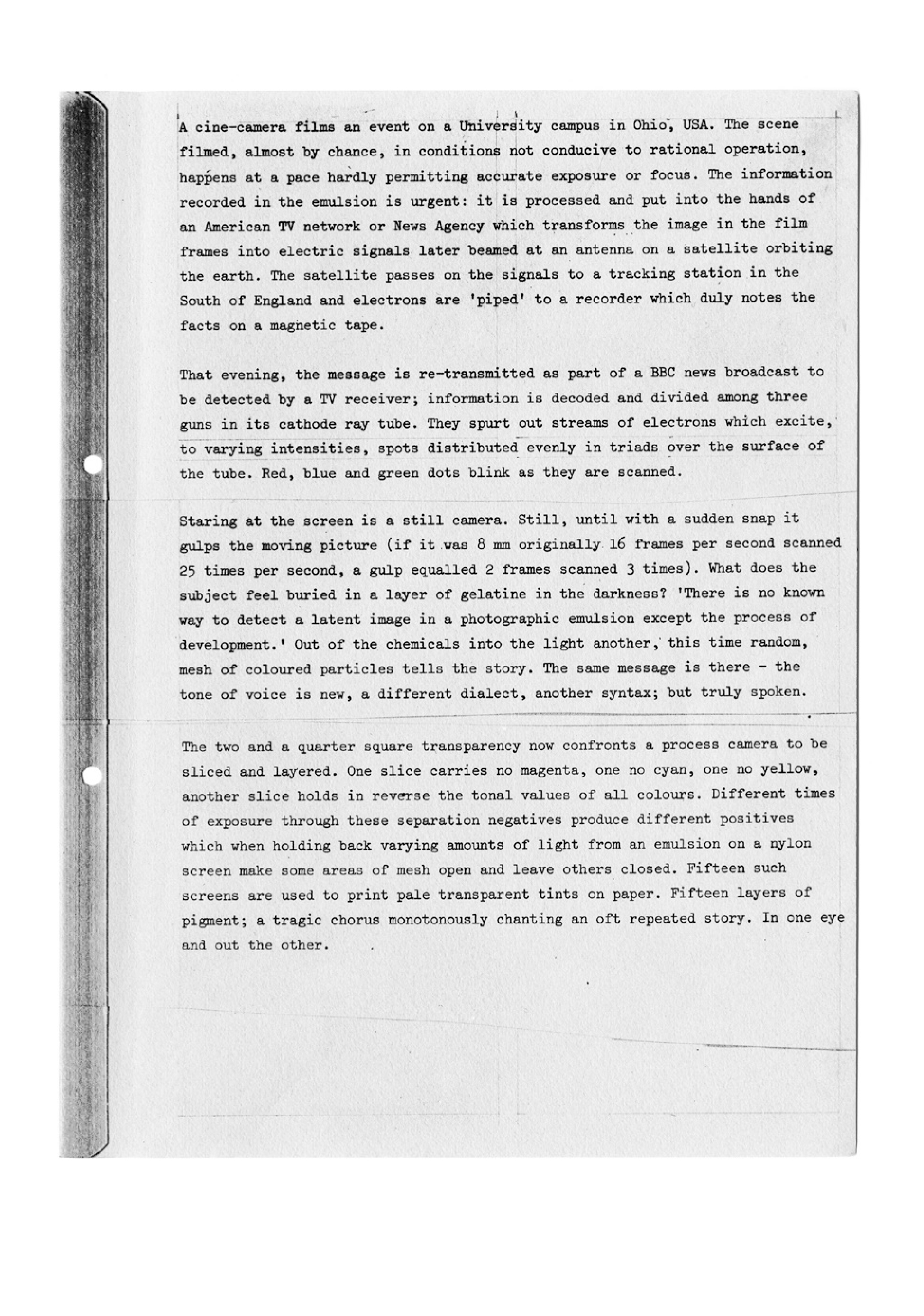

Lead image: Richard Hamilton’s typescript for Kent State (1970).

*

In 1970, the late British Pop artist Richard Hamilton coolly recounted this chain of events in order to tease out the implications of his 15-layer silkscreen print, Kent State.

He had set up a photographic camera in front of his TV set at home, and over the course of a week of evenings waited patiently for an image to suggest itself as source material for further work. The camera had already snapped a number of exposures from a variety of sports, entertainment, and current affairs programs before footage of the shootings by National Guardsmen of students at Kent State University in Ohio (during a protest against the US military’s Cambodian Campaign) was screened on the news on Monday, May 4. The frame Hamilton finally developed shows the top half of the body of one of the shot students prostrate on the ground, head turned towards the amateur cine-camera that originally recorded the moment.

Given the gravity of the event, Hamilton deliberated, but anyway resolved to press ahead and make use of the shot—the questionable “arty treatment” of which, he supposed, might at least serve as a lasting indictment. In the screenprint that emerged several channels of transmission (and 15 layers of ink) later, Hamilton made sure to leave the curved, distorted edges of the cathode ray display within the black surround of his photo of the screen. He also positioned the rectangular shot on the left hand side of the printed sheet to mimic the off-center screen typical of that era’s TV sets. The image is thus “framed” five times over in the final print: first by the original cinecamera, second by the television, third by Hamilton’s photo-camera, fourth by the implied TV on the screenprint, fifth by the printed sheet itself—plus a sixth if you include the frame that encases the print when hung on a wall.

Hamilton’s procedural account stops short, too, of listing itself as the latest in the line of transmission—the perpetuation and degeneration of the image as representation now transposed to text; not to mention its carrier, a typewritten A4 sheet; nor the scan of a photocopy of that original sheet in a plastic hole-punched sleeve on the page previous to the one your eye is now scanning, which you either downloaded as a PDF and are reading in the form of assembled pixels of light on an LCD screen of some description, or as laser-or inkjet-printed carbon on paper, or maybe lithographically reproduced as part of the hard copy edition of this issue; and finally in the precarious form of the apprehension of this entire 45-year-long process you now carry in your mind.

*