(Only An Attitude of Orientation)

2009

Lead image by Frances Stark.

*

Like its predecessor, this pamphlet aims to provoke a discussion around how a contemporary art/design school might reasonably reconfigure itself in light of recent and projected changes in how institutions and disciplines actually operate in the early 21st century.

Here’s an oppurtunity to freely imagine what should be done, unhindered by administrative worries about what can’t possibly be done. (Stark, 2007)

The premise of “Towards a Critical Faculty” was to attempt to grasp what my colleagues meant by “design thinking.” Though I initially considered this term a tautology, they considered it a major aim of contemporary art/design education. And so I ended up trying to perform what I presumed it meant—a kind of loose, cross-disciplinary problem solving—by collecting past and present fragments of insight that I thought ought to inform a future mandate. Where the majority of those excerpts were directly concerned with pedagogy, from seminal Arts & Crafts and Bauhaus statements onwards, this follow-up looks further afield, seeking tangential reinforcement and extension of the same line of thinking. Its sources are drawn from the poppier end of sociology, philosophy, and literature. In fact, most of its sources touch on all three.

If the first pamphlet tried to summarize the lay of the land, this one tries to summon the outcome its inhabitants might be teaching towards. Readers are referred to the disclaimers listed the first time around, and are particularly asked to bear with my sidestepping such basic distinctions as art/design and under/postgraduate. Although I think this reflects the general confusion, the idea isn’t to perpetuate it—only to focus the energies of this reader elsewhere for the time being. I should, however, add one new point: this approach isn’t against teaching basic skills and techniques (whether analogue or digital), history or theory, only for an explicit consensus regarding the whole those components are supposed to constitute. Before beginning, I’d like to reiterate that these pamphlets make no claim to authority, only to engage and entertain both staff and students—ideally at the same time.

...

1. Pragmatism

Although I consider this pamphlet a reader like the last one, this time I’m going to paraphrase its sources instead of directly quoting them, hoping to absorb their lessons deeply enough to pass them on with conviction. Actually, I’m going to start two layers out, by paraphrasing my colleague David Reinfurt paraphrasing William James, the American philosopher who began his famous series of lectures on Pragmatism with the following anecdote.

On a camping trip, James returns from a walk to find his fellow campers engaged in a hypothetical dispute about a man, a tree, and a squirrel. The squirrel is clinging to one side of the tree and the man is directly opposite on the other side of it. Every time the man moves around the tree to glimpse the squirrel, it moves equally as fast in the opposite direction. While it’s evident that the man goes round the tree, the argument revolves around the question: does he go round the squirrel? The group is divided on the issue, and James is called upon to make the casting vote.

The philosopher recalls the adage “whenever you meet a contradiction you must make a distinction,” and proclaims that the correct answer depends on what the group agrees “going round” actually means. There are two possibilities: if taken to mean passing to the north then east then south then west, then the man does go round the squirrel; if taken to mean being in front then to the left then behind then to the right, then he does not. Make the distinction, says James, and there is no ambiguity—both parties are right or wrong depending on how the verb “to go round” is practically conceived. The key here is the word “practically,” as James’s point is precisely founded on hard facts rather than soft abstractions.

James recounts the anecdote because it provides a “peculiarly simple” example of the pragmatic method. I was first introduced to the idea by David, who opened his own lecture with the same story. Titled “Naïve Set Theory,” this talk comprised three parts, each a compressed story of a man’s lasting contribution to his discipline, as chronicled in a particular book. To cut this short story even shorter, these were: William James’s conception of Pragmatic (as opposed to Rationalist) philosophy, Kurt Gödel’s Naïve (as opposed to Axiomatic) approach to mathematics, and Paul R. Halmos’s Naïve (as opposed to Axiomatic) approach to logic. By the end of the talk it’s clear that, despite hopping across disciplines and skirting around some quite complex ideas (at least for newcomers), each example is an articulation of the same basic idea: that the ongoing process of attempting to understand—though never really understanding completely—is absolutely productive. The relentless attempt to understand is what keeps any practice moving forward.

James’s (and David’s) attitude is marked by both a rejection of absolute truths, and faith in verifiable facts. This is staunch empiricist thinking, founded on the notion that “beliefs” are—practically speaking—“rules for action,” and that we need only perceive their potential function and/or outcome in order to determine their significance. James sums up the pragmatic method as only an attitude of orientation, of looking away from first things (preconceptions, principles, categories) and towards last things (results, fruits, and consequences).

There are two introductory points to draw from this. First, that an attitude like empiricism might be usefully identified and its implications drawn out and considered across disciplines. Second, that it’s useful to start with the result in mind and work backwards, in order to design a method oriented towards achieving that outcome. And so in accordance with both: the hoped-for results of our as-yet phantom course are precisely the attitudes demonstrated by the following examples.

...

2. Discomfort

In 2001 the British cultural critic Michael Bracewell published The Nineties, an account of the decade’s art, society, and, in particular, pop culture. In an introductory conversation between two “culture-vulturing city slickers” that frames the rest of the book, one remarks to the other that culture is “wound on an ever-tightening coil.” He’s referring to the momentum of art assimilating and reproducing itself according to the logic of the phrase “Pop will eat itself” (itself the name of a very nineties’ band). This account of unprecedented cultural self-consciousness is backed up by a list of dominant trends, that include the subtle shift from yuppie bullishness to its rehabilitation as “attitude”; irony supplanted by “authenticity” as the temper of the zeitgeist, most patently manifest in Reality and Conflict TV; and the encroaching sense of culture having been distinctly designed by media, retail or advertising—a state of high mediation, of “culture” wrapped in quotation marks. In other words, Bracewell argues, millenial culture is characterized by how it wants to project itself, how it wants to appear to be rather than just being what it is, and this gap between appearance and actuality is getting bigger.

Largely assembled from a collection of concise, diverse profiles originally written for a variety of style and Sunday supplement magazines during the decade itself, The Nineties operates at an odd speed. The book combines the immediacy and involvement of real-time journalism with the delay and detachment of reflective commentary. Its affairs remain too recent, and their effects too tangible, to be considered at a comfortable remove, as “history.” Considered in relation to a school with an obvious stake in contemporary culture, what we might call the book’s keen disinterest in immediate history offers a working model, an editorial premise that aims to register the condition in situ—or as close as seems feasible.

One of Bracewell’s more vivid conceits is to isolate “frothy coffee” as the decade’s all-purpose signifier, one of a few infantile treats he suggests amount to the “Trojan Horse of cultural materialism.” On reading this, a friend noted the not unlikely scenario of reading about what Bracewell calls the “Death by Cappucino effect” while drinking a cappucino, and it occurred to me that in an art/design school, such discomfiting self-awareness might be harnessed towards realizing a sense of “criticism” more pertinent than the usual discussion of work within whatever disciplinary vacuum. A “criticism,” rather, that refers to the ability and inclination to confront, engage with, and communally discuss a subject as it happens—whether a piece of work, a cultural condition, or the relation between the two. The end of Bracewell’s summary seems to call for as much, diagnosing the cumulative outcome of the nineties as “post-political,” a state of impotence characterized by a “fear of subjectivity.” Slavoj Žižek similarly evokes a state where reflection and reflexivity have been undermined to such an extent that “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of Capitalism.” The aim of this exercise would be to nurture this critical attitude in view of reinstating a more athletic sense of agency.

In his essay “Cybernetics and Ghosts,” Italo Calvino describes the constructive generosity of literature that deliberately sets out to disorient its reader. He argues that by means of recursion, involution, and other heady techniques of metafiction, the labyrinthine constructions of such as Alain Robbe-Grillet and Jorge Luis Borges lead away from any comfortable sense of narrative continuum, and that the effort of maintaining a mental grasp on the writing, of constantly reorienting oneself to cope, constitutes its own very particular aesthetic experience. Such experience has obvious pedagogical implications, and Calvino himself referred to such techniques as a kind of “training for survival.”

...

3. Definition

Calvino is essentially describing (and promoting) the process of making a form strange in order to resist both one’s own preconceptions and the weight of others’ opinions. (“Make it new,” as Ezra Pound famously translated Copernicus.)

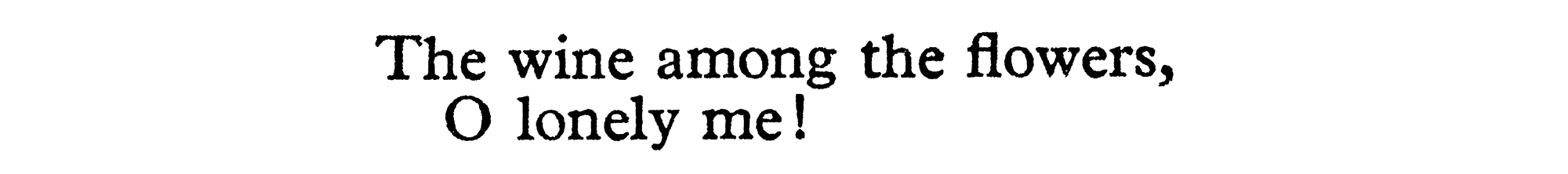

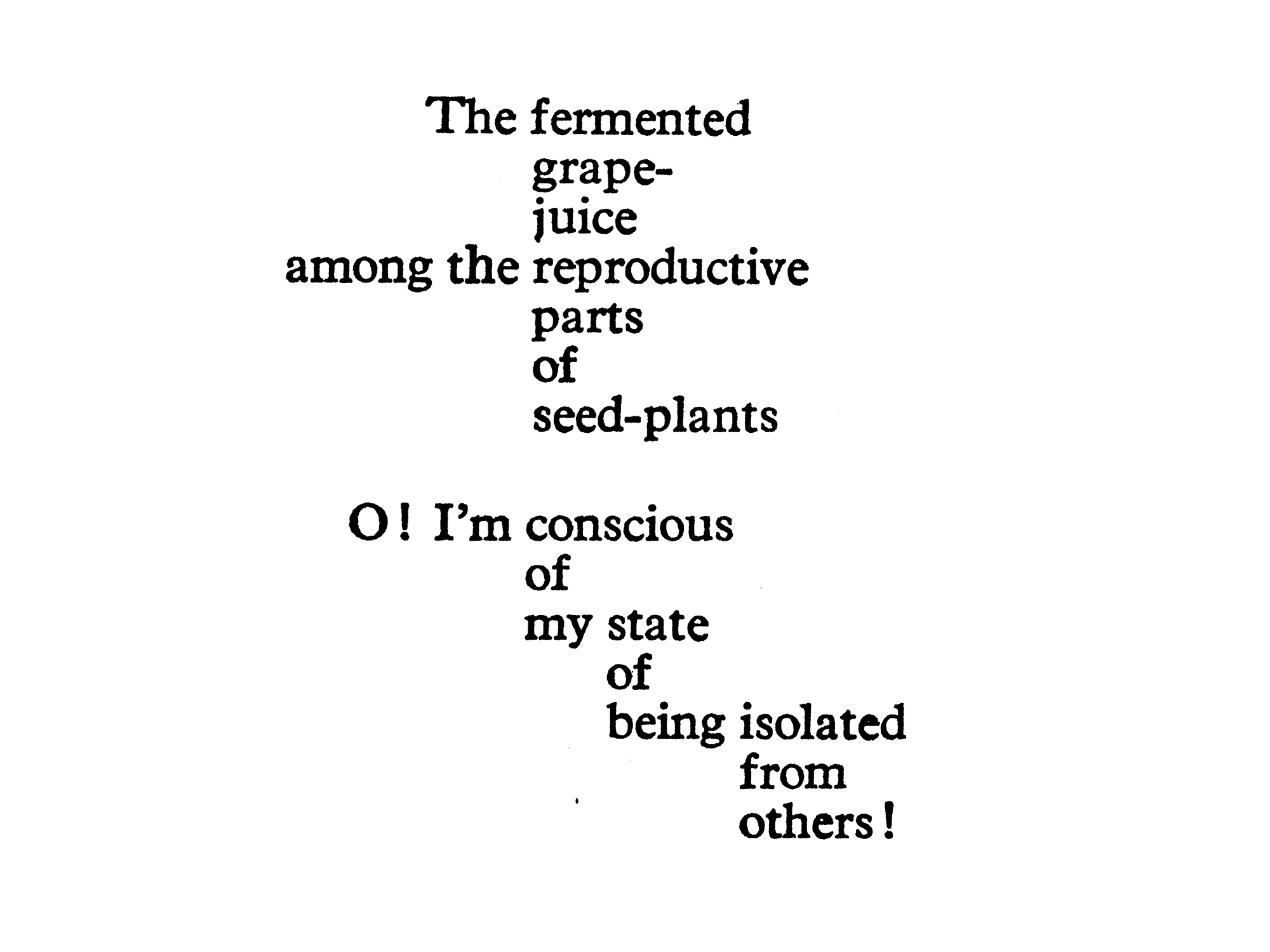

A usefully exaggerated example of this is Semantic Translation, a poetic technique conceived by the Polish writer, film-maker and publisher Stefan Themerson, that manages to be at once ferociously ironic and straight-up hilarous. According to its inventor, Semantic Poetry Translation (SPT) is “a machine made using certain parts of my brain,” as demonstrated most prominently his novella Bayamus. Fundamentally, SPT takes a grey area of meaning and attempts to pinpoint and clarify it. He introduces the process in order to reclaim poetry from the mouths of “political demagogues” who in the twentieth century began to adopt the tools of poets—repetition, alliteration, etc.—towards their own dubious ends. The idea is to restore emptied-out words, clichés and platitudes with their fullest, specific meanings by supplanting them with their precise, verbose dictionary definitions. The method is usually demonstrated by comparing existing poems or songs with a semantically translated version.

For example, from this:

—to this:

But Semantic Translation is more double-edged than this brief description suggests. Although it is ostensibly an attempt to reclaim the “truth” behind words, the proposition is essentially ironic, not proselytizing. It’s more accurate to say that at best “truths” are more properly “beliefs,” and that beliefs should be treated with the utmost suspicion. One of the great benefits of the technique is that it reminds us how “the world is more complicated than the language we use to talk about it.” The nature of reading through the pedantic extent of a piece of Semantic Translation is to experience language made strange, to perceive both its technical depth along with its limitations. Themerson referred to the process as “scratching the form to reveal the content.”

In an astute summary of Themerson’s intentions, Mike Sperlinger recently noted that his promotion of “clarification of meaning” is essentially parodic. The clarification that’s actually happening, says Sperlinger, is that it’s impossible to “truly” clarify meaning because “meaning is always going to escape and proliferate.” I had this in mind when recently asked to write a definition of Graphic Design for a new Design Dictionary. I used the oppurtunity to attempt a discipline-specific overview in the same candid spirit as Bracewell’s culture-wide Nineties, i.e. to summarize the general landscape as plainly and accurately as possible, as opposed to the version a school administration would advertise (whether to sell to parents or students). Here’s an excerpt:

Rather than the way things work, Graphic Design is still largely (popularly) perceived as referring to the way things look: surface, style, and increasingly, spin. It is written about and documented largely in terms of its representation of the zeitgeist. In recent decades, Graphic Design has become associated foremost with commerce, becoming virtually synonymous with corporate identity and advertising, while its role in more intellectual pursuits is increasingly marginalized. Furthermore, through a complex of factors character-istic of late Capitalism, many of the more strategic aspects of Graphic Design are undertaken by those working in “middle-management” positions, typically Public Relations or Marketing departments. Under these conditions, those working under the title Graphic Designer fulfill only the production (typesetting, page makeup, programming) at the tail-end of this system.

On the other hand, in line with the ubiquitous fragmentation of post-industrial society into ever-smaller coteries, there exists an international scene of Graphic Designers who typically make work independent of the traditional external commission, in self-directed or collaborative projects with colleagues in neighboring disciplines. Such work is typically marked by its experimental and personal nature, generally well-documented and circulated in a wide range of media.

As these two aspects of Graphic Design—the overtly commercial and the overtly marginal—grow increasingly distinct, this schizophrenia renders the term increasingly vague and useless. At best, this implies that the term ought always to be distinctly qualified by the context of its use.

...

4. Other schools

Clearly this definition of “Graphic Design” isn’t particularly definitive. The meaning leaks so much that I have a hard time imagining the term it elaborates being usefully applied at all. However, in considering how the recognition and articulation of this confusion might inform an educational program, two possibilities suggest themselves. The first is essentially reactionary: to design distinct courses for the overtly commercial and overtly marginal (“intellectual”?) trajectories, dispensing with the illusion that they can be combined. The second is fundamentally progressive: to operate outside these existing categories, the point being to propose different ways of thinking altogether.

In his book The Shape of Time, the art historian George Kubler proposed a model which broke apart and reconstituted the prevailing compartmentalization of the arts. In his new system, architecture and packaging—both essentially containers—were conflated under the rubric “Envelopes,” all small solids and containers under “Sculpture,” and all work on a flat plane under “Painting.” These re-classifications already fell within Kubler’s broader call to supplant the regular distinction of Useless (=art) and Useful (=design) with Desirable (=objects that last) and Non-desirable (=objects that don’t last). His new system emphasized artefacts that stood the test of time, regardless of whether they fulfilled a more quantifiable purpose (a hammer) or a less quantifiable one (a painting). Alternatively, in What is a designer, the self-described cabinet-maker Norman Potter distinguished between “Things,” “Places,” and “Messages.” So far as I know, neither system was pursued beyond these two books, but they remain useful places to begin the productive destabilization of prevailing classification.

One contemporary model that appears to operate on this principle is Cittadellarte, an institution in Biella, Italy, which was set up by the artist Michelangelo Pistoletto in 1998. The name is a contraction of the Italian words for “city” and “citadel”—a semantic paradox and an example of what Michel Foucault called a “heterotopia.” A heterotopia is a space that is in some sense open and closed at the same time (his prime example is a cruise ship). Comprised of apparently contradictory qualities, a heterotopia is by definition outside the norm. Cittadellarte’s aim is explicitly earnest: to directly question and effect the contemporary role of art in society by operating as a “mediator” between the arts and other fields such as politics, science, education, and economics. It is organized into uffizi—offices with irregular titles like Nourishment, Spirituality, and Work next to Architecture and Fashion. Participants pass through for varying amounts of time to participate in projects involving local, national, and international businessmen, politicians, economists, and so on. The whole enterprise is thus couched in a global ambition that flavours its pithy slogans: “Art at the centre of a socially responsible transformation,” “Italian enterprise is a cultural mission,” “The artist as the sponsor of thought.”

..

5. Group exercise

After reading my dictionary definition of Graphic Design, a friend told me it was far too subjective and that I might productively subject it to an “objective” Semantic Translation. I outsourced the task to a group of design students in California, partly in order to find out how accurate they thought my original description was, and partly because I thought it would be useful for them to make their own free translations. I split the long definition into bite-size sentences and randomly assigned them to the class. Here’s one small excerpt from my original text:

Furthermore, through a complex of factors characteristic of late capitalism, many of the more strategic aspects of Graphic Design are undertaken by those working in “middle-management” positions, typically Public Relations or Marketing departments.

—and here’s its Semantic Translation by one of the students:

In addition, through a group of related circumstances contributing to the descriptions of recent profit-based trade, many of the more carefully planned features of the art or profession of visual communication that combines images, words, or ideas, are undertaken by those earning income at the level just below that of senior administrators, typically those helping to maintain a favorable public image or those in the territorial divisions of an aggregate of functions involved in moving goods from producer to consumer.

I can’t say the exercise changed my mind about the definition, but it seemed productive for the class. Because so many of the sentences dispersed among the students contained the same terms (not least “Graphic Design” itself), when we came to recombine them back into a single collectively-translated monster composite, the individual “definitions” of the same word were so diverse that we were forced to decide on one (which actually meant making a single amalgamation of a few) in order to make the new whole clear and consistent. In other words, we were forced to transform a batch of relatively specific meanings into more diffuse, diluted, ambiguous, and abstract ones when combined for wider use—a practical lesson in the symbiotic implications of definition and democracy.

Another friend argued that my definition pulled its punches by not pointing out that the overtly commercial and overtly marginal poles of Graphic Design are equally impotent. The former because the kind of work commissioned by large corporations and other mainly commercial enterprises has become utterly bland and innocuous, stuck in a loop of catering to market-researched demands that are themselves based on desires based on the previous round of market-researched demands, and so on. The latter (marginal) because its intellectual collateral—personal interest and investment—is predominantly hobbyist, and so devoid of any social or political motivation or efficacy. In his view, the role of designers has rotated 180 degrees from solving problems to creating desires, and regardless of whether these desires are pointed towards commercial or intellectual ends, they are always surplus, i.e. unnecessary, lacking urgency. He proposes that the contemporary designer ought instead to design him- or herself into a third role, essentially a “research” position that focuses on forging purely speculative projects without any obligation to produce actual products.

...

6. Well-adjusted

In 2005 the American novelist David Foster Wallace delivered a commencement speech at Kenyon College, Ohio. A staple of U.S. graduation, these speeches typically involve a public figure or alumnus offering ceremonial wisdom and advice to the graduating class. Characteristically, Wallace simultaneously embraces and parodies the format, cross-examining the clichés in search of genuine affirmation and benefit. In other words, he scratches the form to reveal some content.

The speech begins with a requisite moral epigram—the difference being that Wallace acknowledges he’s beginning with a requisite moral epigram. He continues in this self-reflexive vein, unfolding what’s effectively a meta-commencement speech—and it becomes increasingly clear that Wallace is working something out for himself as much as his audience. As such, he speaks with intimate conviction.

So two young fish are swimming past an old fish, who says, “Morning boys! How’s the water?” When the old fish has passed, one of the young ones asks the other, “What the hell is water?”

The anecdote sets up Wallace’s key themes: the awareness of self and surroundings; the task (and difficulty and pain) of maintaining such awareness on a daily basis in the post-collegiate Real World; and the consequent realization that YOU are not the center of the universe but one of a community with equivalent needs and desires and frustrations—an idea that’s as patently obvious as it is difficult to act as if aware of it.

With this in mind, Wallace calls into question the actual value—and so the fundamental purpose—of the kind of liberal arts education the Kenyon students are about to complete. He deconstructs another cliché in response, positing that the apparently trite, even patronizing idea that a liberal arts course teaches you how to think is actually eminently practical and productive if considered in the sense of the ability to choose what to think about and how to go about doing so.

He illustrates the point by recounting a regular adult evening, exhausted from work, driving to buy groceries, and having to deal with a number of banal frustrations along the way: traffic, muzak, disorganization, screaming kids, rudeness. Our “default setting,” he says, is to view these obstacles as set up against You in particular, to get frustrated and angry, and to direct that frustration and anger at others whose existence appears (from the point of view of this state of mind) to be solely geared towards preventing You from doing what You need to do. The privilege that “learning how to think” affords, he says, is the possibility of realizing those around you in the supermarket/world are in all likelihood experiencing their own markedly similar frustrations. And so you might coax yourself into thinking and acting with benevolence rather than rage.

Wallace is careful to point out how “extraordinarily difficult” such humility and self-discipline is; and that, despite his supposedly exalted position as commencement speaker, he’s no model in this regard. His story is a peculiarly simple example of the virtue of self-awareness—as a mechanism for coping with the adult fact of being “uniquely, completely, imperially alone.” This state of quotidian grace, he says, is what we mean when we refer to someone as being “well-adjusted.”

...

7. Solitude

In the “P for Professor” section of Abécédaire, a testimonial interview made for French TV, Gilles Deleuze discusses his work as a teacher. In the first of three moments of unscripted insight, he describes the enormous amount of preparation required to “get something into one’s head” just enough—to a teetering degree of comprehension—to be able to convey it to a class with the sort of inspiration that only comes with live realization. This preparatory work is like a rehearsal for a performance, he says—a planned improvisation. If the speaker doesn’t find what he’s saying of interest himself, no one else will. The ideal is to learn something while conveying it, he adds, though this shouldn’t be mistaken for vanity; it’s not a case of finding oneself passionate and interesting, only the subject matter.

Later, Deleuze draws a distinction between schools and movements. A school, he says, is a typically negative force characterized by authority, hierarchy and bureaucracy, and so is heavy, fixed and exclusive. While a movement is less easily defined, he continues, it generally alludes more to intentions, attitudes and the passage of ideas, and is therefore comparatively light, flexible and open. Surrealism was a model school and André Breton acted as its headmaster—imposing rules, sacking staff and settling scores. Dada, on the other hand was an exemplary movement—a flow of ideas that continues to touch many people, places and forms still happily devoid of any sense of overriding order.

Deleuze’s final insight in “P for Professor” recalls Wallace’s musing on solitude. In Deleuze’s experience, the immature student is drawn to enroll in a school primarily as a consequence of “being alone.” Lacking the sophistication to think otherwise, school is understood above all as an opportunity to participate in a community. Deleuze, however, considers it his job to foster the opposite—to reconcile the student with his or her solitude by teaching them the nature of its benefits. To this end, Deleuze emphatically circulated philosophical concepts in his lectures and seminars—not in view of eventually establishing them (which would be to turn them into a “school of thought”) but in the hope that they might be applied and manipulated by others according to their own sovereign interests and talents, and so remain perpetually in movement.

...

8. Trial & error

Established in Arnhem in 1998, the postgraduate design school Werkplaats Typografie (Typography Workshop) is an example of an institution founded on apparently ideal conditions: officially affiliated to the local art school and so sufficiently funded, yet physically and spiritually autonomous. In theory at least, it seems ideally placed to cultivate Deleuze’s “movement” and avoid the drag of his “school.” As one of its initial clutch of students, and having maintained irregular contact with its teachers and subsequent participants since, I’ve been able to follow its progress both first- and second-hand. In fact, I’ve been invited to write about it for one context or another in handy five-year intervals; each occasion has been an excuse to note my changing ideas about the place, about what’s actually happened from conception to current incarnation.

The first, “Incubation of a Workshop” was written in 1998 from the vantage of an idealistic student in the first of his two years in an institution under construction. It’s a kind of prose home movie that documents the essential openness of the place in progress, emphasizing its quirky, homegrown nature, lack of hierarchy and purported “two-way teaching” between not-quite-teachers and not-quite-students. The Werkplaats’ founding idea was to set up an art/design school based on real (=commissioned) work rather than fictional or self-directed projects, because only this connection with the outside provides the “correct sense of requiredness” necessary to make substantial, meaningful work.

In 2003, “Some False Starts” was written as the introduction to a book that accompanied what its by now mildly jaded author thought was a too-soon “retrospective” of work at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. It begins by denouncing the “relentless sugary pitch,” “wide-eyed positivity”and “woolly moralism” of the previous essay, then tries to recount what had actually happened since, despite those good intentions. Tentatively tucked away in the middle is a coy criticism of the WT’s increasing obsession with its own image and “supression of mistakes.” (The writer thinks any real art or design school ought, on the contrary, to make the most of its mistakes.) A few arguments and excursions are recounted, with each negative offset by a positive. “It was all human enough in the end,” he shrugs, and it’s clear that early idealism has shifted to late accommodation.

Finally, in 2008, an “Errata” for the school’s tenth anniversary book essentially amounts to a reconsideration of such self-aggrandizing which, it seemed to me, had now become a large part of the whole point of the place. Otherwise put, relentless self-reflection seemed to have become its defining characteristic: it was now a school about school, more concerned its own working principles than outside work. This is manifest not only by their publishing yet another autobiography in the first place, but also by the work shown in it—which “runs a small gamut from the very local to the very personal.” I used to think this was disappointingly narcissistic or solipsistic, but now I consider it more affirmatively symptomatic of a discipline (or a few blurred disciplines) between states, a little lost, trying to work out what it has been, is, and might become. In lieu of any seemingly worthwhile work from the wider world, the overwhelmingly local nature of all the self-initiated books, posters for visiting lecturers and flyers for film screenings that pack the book’s pages suggest that the WT’s principal aim has simply (and complexly) become “community-building”—in search of Deleuze’s reconciliation with solitude. This, then, is an instance of a school currently experiencing a reflexive reconsideration of its founding discipline. I’m not sure how much the school realizes this itself, or needs to, really, but the process could certainly be admitted and utilized elsewhere.

...

9. The demonstrator

I’ll close with some incidents from the classroom scenes in Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, as they usefully summarize the component attitudes related so far in this document:

pragmatic ways of dealing with objective facts

the discomfiting observation and articulation of the current condition while participating in it

the deliberate disruption of received wisdom by making it productively strange

the collective redefinition of the situation

to establish a new set of terms

towards a well-adjusted awareness of self and surroundings

the communal participation towards an individual reconciliation with solitude

through deliberate trial and error that constitutes a “lesson”

In one particular passage, Robert M. Pirsig’s alter-ego-protagonist-teacher Phaedrus assigns his undergraduate class in rhetoric an expansive but straightforward task: to write an essay on some aspect of the United States. He becomes preoccupied with one particular girl who, despite a reputation for being serious and hardworking, finds herself in a state of perpetual crisis, unable to think of “anything to say.” He obliquely recognizes in her block something of his own paralysis in not being able to think of “anything to say” back to by way of help beyond suggesting a subject—the local Opera House. This doesn’t help her either, but after next proposing out of sheer frustration that she should focus on a single brick, something gives and the student produces a long, substantial essay about the front of the building. Initially baffled by his own involuntary insight, Phaedrus reasons that she was blocked by the expectation that she ought to be repeating something already stated elsewhere, and freed by the comic extremity of his suggestion. There was no obvious precedent to an essay about this particular brick, therefore no right or wrong way to go about it, and so no phantom standard to measure up to. By this curious, circuitous, yet perfectly logical method, the student is liberated to see for herself and act independently. In this way, Pirsig/Phaedrus instructively enacts his bald reconsideration of the question “how to teach?” in front of the students he’s trying to teach.

He continues to perform variations on this exercise with the rest of his class (“write about the back of your thumb for an hour”), which yield similar results, and concludes that this tacit expectation of imitation is the real barrier to uninhibited engagement, active participation and plausible progress.

A few further scenes of fraught but instructive trial and error conclude with his fundamental consideration of the nature of “quality,” the cornerstone implied by the book’s subtitle, “an inquiry into values.” Through a series of simple exercises he first proves to the class that they all recognize quality, because they routinely make basic quality judgements themselves whether they realize it or not. Then he assigns the essay question “What is quality?,” and counters their angry response that he should be telling them, not the other way round, by admitting that actually he has no idea himself and genuinely hoped someone might come up with a good answer. A few days later, though, he does draft his own self-annulling definition: because quality is essentially felt, i.e. a non-thinking process, and because—conversely—definitions are the product of formal thinking, by definition quality can not be defined. This leads him to respond to his students’ perpetual question, “How do I make something of quality?” (like a decent piece of writing) with “It doesn’t matter how it’s quality as long as it is quality!”; and to “But how will I know it is?” with “Because you’ll just know—you just proved to me you make judgements all the time.” The student is thus lured into forming his or her own opinions based on their own inherent sense of quality. “It was just exactly this and nothing else,” he concludes, “that taught him to write.”

...

To duplicate the end of the first pamphlet: consider a reconstituted art/design foundation course based on the qualities described in this one—a curriculum that embraces as much sociology, philosophy and literature as art and design, as demonstrated here. Supplanting those outdated approaches to art/design education, this new foundation might involve its students self-reflexively designing their own program as an intrinsic part of its instruction—towards the development of a “critical faculty” in both senses of the term.

*

Between presenting all the above as a fairly incoherent talk at Michigan State University in Winter 2008/9 and writing it down a year later, I read Jacques Rancière’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster in heartening confirmation of the trajectory suggested so far. In line with the rest of the paraphrasing in this pamphlet, it seems useful to distill the book’s main points to serve as a timely postscript.

Subtitled Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation, Rancière’s book tells the story of Joseph Jacotot, a French school-teacher who, by an inspired accident, finds that he’s able to teach things he doesn’t know himself. In exile from France in the wake of the Restoration, Jacotot was invited to teach a class at a university in the Flemish town of Louvain. Because neither he nor his students spoke the other’s language, Jacotot searched for a common item to serve as a teaching tool, and came up with a recent bilingual edition of François Fénelon’s adaptation of Homer’s Telemachus. He then set his class the task of reading and discussing it in French.

Starting with the first word, relating it to the next, then deducing the relationships between individual letters to form words, words to form sentences, and so on, Jacotot made his students discuss the work they were learning—initially reciting it by heart, then using terms derived from the text itself. The experiment was a success: within a couple of months his students had a substantial grasp of both the book and the French language. The learning process, Jacotot observed, was played out strictly between Fénelon’s intelligence and the students’ intelligence, essentially without his mediation. This led him to conclude that “everything is in everything”—a principle that recognizes the fundamental commensurability and relativity between things. Once something—anything—is learned, it can be compared and related to everything else. Jacotot’s role as “master” involved little more than directing the students’ inherent will to learn by asking them to continually respond to three questions: 1. What do you see? 2. What do you think of it? 3. What do you make of it?

Jacotot’s method was thus founded on an very rudimentary idea: because the art of Telemachus was the product of a natural aptitude common to all humans, everything required to “understand” it—for the transmission of a writer’s ideas to a reader’s mind—was contained within itself. The book didn’t require explication from a third party (a figure Rancière calls the “old master,” a cipher for prevailing approaches to pedagogy). In other words, the work could speak for itself, and with adequate attention anyone could understand it. Every willing student possesses the same natural savvy to comprehed an artefact in the same way he or she had autodidactically learned to speak as a child: via an initially blind process of mimicking, repeating, correcting, and confirming in order to interact meaningfully with another human with the same basic intelligence.

These ideas became the foundation of what Jacotot called “universal teaching.” All humans are equally intelligent, he surmised, and the unfulfilled potential of this intelligence is only ever the result of laziness or distraction, compounded by the myth of personal inferiority or incapability. The phrase “I can’t,” says Jacotot/Rancière, is meaningless. Anything can be learned by anyone propelled by desire or constraint. What is commonly called “ignorance” is more correctly diagnosed as “self-contempt”—the notion that an individual doesn’t have the “ability” or even “right” to learn by or for him- or herself. The Old Master’s method was based on what Jacotot/Rancière calls “stultification,” whereby the teacher constantly withholds “knowledge” supposedly too difficult for the student to understand, revealing and explicating little by little, careful to always remain a step ahead. This technique is at once analogous to and the cause of any general social order founded on inequality, manifest in the greater or lesser possession of, say, knowledge, power, or money.

Universal teaching is founded on equality as a presupposition rather than a goal. Jacotot’s method, and Rancière’s resuscitation of it, thus amounts to a position at once philosophical, pedagocial, and political. Where the Old Master maintains the division between the supposedly “wise” and the supposedly “ignorant,” the new model proposes emancipation, first via the simple realization that one is capable of learning, then the ability to educate oneself by observing the relations between empirical facts. Instead of meekly accepting received wisdom, the emancipated student is thus made conscious of the true potential of the human mind—which in turn is the only faculty necessary to emancipate someone else (and so on).

Jacotot/Rancière further insists this method is most suited to being passed on from person to person (ideally parent to child) rather than from one to many (i.e., from an institution to society-at-large). He emphasizes, too, the distinction between private “man” and public “citizen”. The latter will always tend towards entropy, he says, and so always become essentially distracted from the axiom of equality, so whatever the social context, inequalities will always emerge. And while Jacotot/Rancière recognizes the need for social particpation, he holds that the emancipated man is always simultaneously disinterested, that is, aware enough to remain fundamentally independent.

The most ubiquitous and insiduous form of distraction to undermine universal teaching is the notion of what is commonly called “progress.” Numerous attempts to establish Jacotot’s principles in the 19th century became preoccupied (i.e. distracted) with determining (evaluating, classifying) the degree of his method’s “progressiveness.” It was thus reduced to one stage in a perceived continuum of progression—as a means towards an end rather than an end in itself. It’s this very desire to quantify progress that forces the method back into the pattern of chasing goals, thereby setting up those distracting differences, hierachies, and inevitable inequalities. (There’s a clear parallel here with the present-day mandate to quantify education under the catch-all banner of “research.”)

When the term “emancipation” became equivocal—without any useful common meaning—Jacotot began to refer instead to his teachings as “panecastic” (literally, “everything in each”), and preferred to think of them as “stories” rather than a philosophy or ideology. One of the more artful and affecting aspects of The Ignorant Schoolmaster is noted at the end of translator Kristin Ross’s introduction. She points out that Rancière consciously adopts Jacotot’s technique of storytelling by subtly confusing the narrative voice, which invokes a timeless, compound form of address. Despite regular indications of both full and fragmented quotations (generally attributed to Jacotot only in the endnotes), it becomes increasingly difficult to discern who exactly is “speaking”—Rancière or Jacotot? The implication: the universal idea is speaking, not any particular person.

In this way, Rancière embodies two of the book’s enduring lessons. First, by telling a story rather than writing an essay, he puts himself on the level of the reader, recounting the tale person-to-person rather than philosopher-to-student. Second, by scrambling the voice in this way, he discards the regular idea of accumulated, gradual history (reflected in his rejection of accumulated, gradual education). The impersonal open-sourced paraphrase embodies the positive power of the perpetuation of ideas—a form in which, in whoever’s words, all is and are equal.

*

References:

In the hope of helping the text flow a bit better I decided not to foot- or endnote the many books and articles cited in the texts, but all the relevant references are finally collected here.

Bailey, Stuart, “Incubation of a Workshop,” Emigre, no. 48 (1998); “Some False Starts,” In Alphabetical Order. File Under: Graphic Design, Schools, or Werkplaats Typografie (Rotterdam: NAi, 1993); and “Errata,” Wonder Years (Amsterdam: ROMA, 2008)

Bracewell, Michael, The Nineties: When Surface was Depth (London: Flamingo, 2001)

Calvino, Italo, “Cybernetics and Ghosts” [1967], The Uses of Literature (San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1986)

Erhoff, Michael & Tim Marshall, eds., Design Dictionary (Berlin: Birkhauser, 2008)

Foster Wallace, David, commencement speech, Kenyon college, 2005. An edited version was published as This is Water: Some thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life (New York: Little, Brown, 2009)

James, William, Pragmatism [1907] (London: Signet, 1970)

Pirsig, Robert M., Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (New York: William Morrow, 1974)

Reinfurt, David, “Naïve Set Theory” in Dot Dot Dot, no. 17 (2008)

Singerman, Howard, email to Frances Stark, Introduction to Frances Stark, ed., Primer: On the Future of Art School (Los Angeles: USC, 2007)

Themerson, Stefan, Bayamus (London: Gaberbocchus, 1965)