Right to Burn

2007

This wandering conversation between myself, Sarah Crowner, and Christoph Keller was originally published in Dot Dot Dot 14. It was transcribed from a late night recording on Christoph’s farm Stählemühle, close to Lake Constance in rural Germany, May 2007.

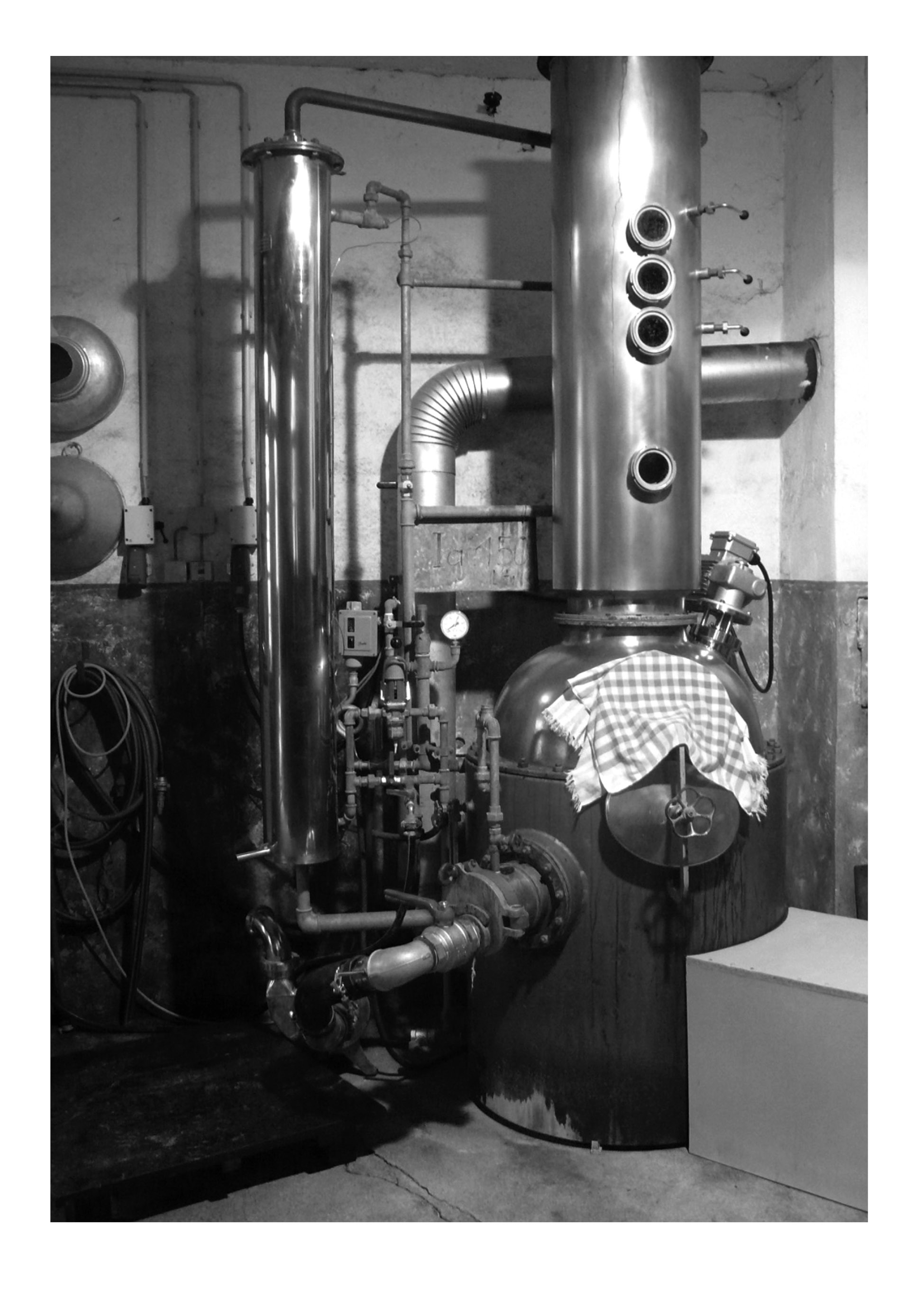

Lead image: The original still at Stählemühle.

*

A bottle is opened

Christoph Keller: Let’s start with something easy. This is a schnapps made from the Black Forest Cherry, which is actually a trademark like Whisky or Champagne, meaning you can’t call it Black Forest Cherry if the fruit isn’t actually from the Black Forest and distilled within the vicinity. I buy them from an organic farmer who lives in one of those incredible valleys which fluctuate between 200 and 1,600 metres, all very dark woods with places where you can’t see any light because it’s so densely forested.

Schwarzwälder Kirschwasser is poured

CK: He has a farm with maybe 30 hectares of cherry trees and machines which hold the trees and shape them. There are huge nets to catch the fruit when it falls, and a kind of giant vacuum cleaner which sucks them all in. There are so many trees—around 4,000 I think—that it’s impossible to harvest them in any other way. The fruit used for distilling is not comparable to normal fruit, because it’s not grown to be eaten, but to be left on the trees as long as possible to get the fullest flavour. It then has to be harvested very quickly just before the rotting starts, when they contain the most sugar and strongest aroma.

All: Cheers. [clink ]

CK: This is also our silver medal winner [laughs ] in the biggest European schnapps event, which is some kind of cross between the Olympic Games and documenta.

Stuart Bailey: And does winning that prize mean you’ve stopped thinking of yourself as a dilettante distiller?

CK: Well, I still believe in the dilettante as a kind of leitmotiv, but obviously if you do something very enthusiastically—even as a dilettante-enthusiast—at some point you produce quality that is so-called professional. Then again, perhaps it doesn’t really apply because we’re working in very small quantities here, maybe 200 bottles. A professional distiller makes more like 1,000 litres or 2,000 bottles, in which case it’s far more difficult to maintain the same quality. But no … in my mind at least it’s still a dilettante hobby.

SB: I presume that you started the art publishing house Revolver as a dilettante too. As you know, I’m interested in the idea of maintaining a state of permanent dilettantism …

Sarah Crowner: Do you prefer that to the idea of the professional?

CK: I’m not actually sure I necessarily prefer it, as such—I’m just like that. As a kid I always did as much stuff as possible … I tried all the sports, all the musical instruments, played around a lot, but at some point always fell off. I never had the guts to keep going through the crisis points, and this was also true of the publishing. That’s very negative, but on the positive side, I’m also very interested in that underlying Renaissance idea—of universal man, scientist, whatever—which has completely changed since digital media. Now studium generale or whatever you want to call it, is so much easier because previously, even before you could research, you had to research how to research—which bibliographies to use, which libraries, and so on, so this is really a landmark. Of course, we also know all the side-effects too—of information being dubiously edited and controlled, and so on, but still the implication is there. With digital media this universal science is increasingly possible, and as a consequence I think I’m personally getting more dilettante every year. The reason I became a publisher, though, was actually through a baseball club which I started at the end of the 1980s after I was an exchange student at a high school in New Jersey. I was fascinated with the sport and so started a team in my hometown near Stuttgart called the Leonberg Lobsters.

Laughter

CK: Then the big question was how to design the uniform, the logo for the cap …

SB: … and the lobster claw was the baseball mitt.

CK: Of course, of course! And that’s how I started to work with the early Corel Draw software—simply because someone had to do it. I found it quite simple and interesting, and I kept on designing stuff for baseball. Later I even made stuff for the Major League Baseball organization to make a living while I was studying art and art history.

SB: That’s odd … I also became involved in a similar way through second-hand American sports. I was in provincial English teams with that same sense of being at least as interested in the badge and the uniform as the sport—not completely, but I think as equally as the game itself.

CK: The physical aesthetic is very much an aspect and an attraction of all the American sports—much more so than soccer, for instance.

SB: Traditionally, yes, but don’t you think the European aesthetic is inevitably going the same way?—inevitable in the sense of society generally approximating American models. I mean, consider the last decade of soccer kits … and international cricket is even more extreme, from the completely white, traditionally neutral non-uniform, to the current vogue for vivid colors.

CK: I only know the soccer ones, to be honest, and they just get worse and worse. Sometimes you see a nicely made one but the turnaround is so fast that they never get established. Jack Daniels was sponsoring St. Pauli the other year, and their shirt was brown with stripes—it was a really beautiful thing, but that was definitely an exception. At the moment Adidas is taking over everything, so they all have these stupid shirts with idiotic collars just to generate this year’s fashion. We all know the story—planned obsolescence is nothing new—but the results are always such crap. The American sports have a much more direct attention to the equipment and fashion, though. What was your local team called?

SB: The Selby Siclones …

Laughter

SB: … as in cyclone, whirlwind … but the important thing was that it wasn’t spelled C-Y but S-I for the visual alliteration.

CK: So it was SS …

SB: Yes, and that’s exactly the same point in terms of language, right?—that the aesthetic of the words is contrived in the same sport-specific way as the uniforms—and soccer teams are appropriately more mundane, so you get Manchester United or Sheffield Wednesday.

CK: Kids would never do anything so specifically American anymore because America is so out of fashion at the moment. As a European teenager growing up in the 1980s, America was still a kind of Golden Land—you’d really aspire to go there, live there … be an American, really … and now it’s changed completely. Not for our generation, but for today’s teenagers. Anyway, back to the question: so I knew how to use Corel Draw …

SB: … and how to run a team …

CK: Right, and the funny thing about my baseball career is that I started as a pitcher …

SB: [laughing ] … and ended up designing the badge!

CK: [laughing ] It’s even worse! We won the championship for five consecutive years, so we kept moving up a one league each time. In the first year I was a pitcher, but by the second year I was already not good enough. In the third year we bought some people from South Africa to play for us, then I became an infielder, then an outfielder, and after that, because my hitting was also not good enough by this point, I became the announcer!—the guy with the microphone to explain to people what’s happening on the field! That’s what you call a downward spiral of dilettantism …

More laughter; a bottle of Marillenbrand apricot spirit is opened and poured

CK: Anyway, by this time in art school everyone would ask me to design—no, not design, to make—them cards or posters or whatever, and two good friends, the artist duo Korpys/Löffler approached me with a series of photographs they’d stolen from a police department which showed apartments used by the Red Army Faction during terrorist activities—bank robberies, kidnappings and so on. They were all completely camouflaged to look like normal 1970s German apartments—like something out of a Fassbinder film, completely zeitgeist. They always had these anterooms which were full of dynamite, walkie-talkies and weapons, which were obviously hidden away, but Korpys/Löffler were only interested in the anonymous ones, in the camouflage, how they did it, what the typical furniture was. They used the same technique the German police invented around the same time—some kind of computer-aided grid used to track terrorists—to find out where these objects in the apartments came from. Anyway, I thought the material was incredible, suggested we should publish them, and they agreed. All I knew about books at this point was that we needed something called an ISBN number so people could order it. It turned out that it was very easy to become a publisher. You just paid 20 German marks at some kind of office for economic administration, and that was it —we could have as many ISBN numbers as we wanted. We printed their book in a edition of 300 copies on my laser printer, then bought an inkjet printer to do the colour plates [laughs ]. It was a huge chaos of production as we were trying to print on both sides, then cut the pages from the sheets. We also had to devise a way of making a spine, as I had this idea—and still do, as a matter of fact—that a book is only a book if it has a spine. We ended up binding it with the Socialist Union printer of Karlsruhe [laughs ] who I suppose we felt closest to, and finally we called the publishing house Revolver because it fitted with the terrorism, but also the notion of a revolving idea, as we intended to make other unknown things in the future.

SC: Did you end up selling the books? Was that even the point?

CK: We had absolutely no idea about selling. I had some idea about what was going on in art because I was working as an artist and with all those people, but I had no idea about books. I simply thought, we make these and sell them, then we do more. Ridiculous, but we had a lucky break when a friend of mine got some money from his parents who were trying to get rid of him. They gave him 30,000 Marks—which is quite cheap [laughs]—and after he lost a bit on the stock market I asked if he was interested in becoming a publisher, and he said, oh, publisher, yeah, yeah, that sounds quite good. He had nothing to do with art or books, in fact he was a musician. It’s a bit like that Bill Drummond story—he also calls himself a publisher when people ask him what he does, since he’s not a musician anymore and he has this odd career. The title comes from when he was in the KLF and they wanted to rent a van but the guy at the rental told them you can’t get a van if you call yourself a band, just say you’re a publisher, so that’s what he did. It’s actually a good term for people like him, as it expresses any kind of work that has both aspects of being public and multiplied.

SB: And was it the same for you?

CK: Not exactly. The German term, Verlag, means something slightly different, because there’s a distinct economic implication. It comes from a banking term, and means giving money to someone with the expectation of a profit—from Verleihen, to loan—but my friend liked the idea of the title, to be something without knowing anything about it. That’s something common to most book publishers: you don’t have to know anything, you don’t have to have any abilities.

SB: I just had a similar experience making a book in perhaps the most autonomous situation you could imagine: a collaboration with an artist where neither the various galleries who paid for it, nor the museum that organized it, nor the publishers who are to distribute it, had any practical involvement with the book whatsoever—none of them even saw it up until it was printed and bound, other than to check their names on the cover … but you can be sure on the day it’s sent to print there’s suddenly a whole discussion and jostling about who’s called what—the editor, the publisher, and the distributor … in that order of prestige. Of course all the words have slightly different meanings in different countries and languages, so the negotiation is very tricky. In the end the solution was agreed upon based on the Museum being called “the producer” in the film industry sense, as distinct from “the director.”

CK: And the publisher would be the equivalent to the film studio—MGM or Warners. Personally speaking, in the books I’ve been involved in, I always want to be called the publisher because even if I don’t invest the money it’s still an investment of time and work. I still put the risk into it.

SB: What does it means exactly—to publish now, in 2007? … I mean, if one party asks another “to publish” what exactly is expected? Money? A distribution network? Some form of caretaking, organizing, enforcement of standards, proofreading … or something else? I like the idea that “risk” is the best answer. The book I mentioned previously is an example from the cusp of this wave of ambivalence where no-one really understands what the precise roles are anymore, everything’s up for grabs and everyone naturally wants to claim the best labels while doing the least amount of work. In the end, of course, the real caretaking—I mean very literally taking care, worrying about a project, a book, rather than “organizing” in a more abstract sense, defaults to the end of the food chain where the genuine interest—or love, really—is. This is a gross generalization, perhaps, but surely rings true to anyone involved in arts publishing at the moment. It’s an extreme shift, and one which goes largely unchecked.

CK: Yes, and also in the last 20 or 30 years there’s a related shift from the publisher being the one who invests, to the whole setup of arts publishing in Europe being subventioned, so it’s always state or public money. That’s the big difference with the U.S., because every book that is made in the art world in Europe is, in one way or another, subventioned by whatever trickle-down effect through the various institutions—publishers, galleries, museums, et cetera—with public money. Never directly, of course, and no-one would ever admit it too explicitly. In the case of Revolver, we started with that friend’s 30,000 Marks, and made eight books with artists we liked in the first year. We had to do it cheaply, of course, but that stage was paradise … we didn’t sell anything and suddenly the money was gone, so we had to change the whole idea, at which point I started to collaborate with institutions. Because they’re all subventioned, however, the nature of the funding directly influences the kinds of books that then get commissioned, the types of artists and subjects. Ultimately if you work for them it sounds like you have a job, but really you’re just part of a system to keep people off the street! In this sense it’s crazy, it’s a problem, but on the other hand, without that money there wouldn’t be a single book on art … or at least a small book would cost maybe 120 Euros if calculated it in direct relation to actual costs.

SB: Why weren’t you selling those early books—because they weren’t being distributed effectively or because no-one wanted them regardless of that?

CK: Well, the idea was to work with really young artists. My idea of the artist’s book was largely Fluxus- and Ed Ruscha-inspired, with the idea of reviving the publication of art in the form of books, outside the usual channels of galleries and other institutions. At that time nobody cared for the people I was working with—Jonathan Monk, Franz Ackermann, Daniel Roth, or Christian Jankowski—so we’d go to art fairs trying to sell the books by hand … and that’s the story of how it didn’t work! Pretty soon we decided to go with a regular distributor, which as you know means you rarely get paid, and even if you do it’s with incredible margins of something like 60 – 40% in their favour. Like everyone else, we did it anyway. One of the audiences we were always aiming at was our generation—meaning students or recent students who might have a little money from time to time to afford a book, but we found out they just don’t exist, so neither site-specific selling nor regular distribution worked, and that was the point where we simply had to discount them. This carried on even up to the last year of Revolver, before I sold it: at that point we had a turnover of half a million Marks, but still only 10% of that was from selling books—the rest was from production services, design services, and suchlike, which had grown up around the publishing. That’s how it works with art books—it has absolutely nothing to do with selling. Nothing.

SB: So essentially you’re making your own work, creating jobs for yourself and your circle; by which I mean to say the essential outcome isn’t the product, isn’t the books, but rather the creation of “work for Revolver”—a kind of backwards industry, perhaps even inverse capitalism, in the sense that it’s about creating jobs rather than products.

CK: Yes, that’s true, but of course in our case the end result is also important because, firstly, they generally are things we’re interested in rather than a randomly desired or marketable product, and secondly because the collective result of those products is to create an aura around the company. All the products have to be good even though they don’t sell. On many occasions I’ve put money into books that I knew I wouldn’t sell more than 20 copies—because they generate a certain idea or respect for what both the book and publishing house stands for.

SB: And who benefits?

CK: With Revolver we were interested in creating the profile of a publishing house, and actually I think this is the only thing an art publisher can really do today—construct a framework or context for an artist. So there are artists who say, quite specifically, I want to be in the Phaidon monograph series, and others who say, I want to be in the most hip publishing house, or most chic magazine—that’s where I belong. That’s why it’s important to set up this profile, why the products have to be right, even if, ecologically and economically, they make no sense, because there’s a sense of balancing the whole field. Revolver was simply an attempt to counteract the existing situation, and I think we actually achieved that, more or less, by the time I bailed out. In my opinion all these big arts publishing houses today aren’t really publishers at all, precisely because they don’t take any risks—they don’t put money in books at all, they only work with funding institutions. The only ones that sell anything in a meaningful way are Taschen, some Phaidon stuff, and a few obvious large scale catalogues. For the rest it’s only about generating marketable contexts, even intellectual contexts, and though it’s not necessarily what we like, it does generate a framework.

SB: What’s next?

CK: A blackcurrant schnapps … which is very time-consuming to make, although they do it in Austria, for some reason. I found this guy on the north shore of Lake Constance who harvests blackcurrants for the Austrian distillers, so we tried making a schnapps with it too.

A bottle of Ribisl blackcurrant schnapps is opened and poured

CK: It has a very strong aroma. In my opinion, though, the smell is better than the taste with this one [laughs ] … but it’s still a bronze medal!

SC: The process of publishing seems to parallel that of distilling. Do you think of these bottles in the same way as the books?

CK: The big difference for me is that for all these years we were making books, inevitably giving them away to people, and the reaction is always, oh yeah, yeah, nice, good … thanks … and that’s it. With a bottle of schnapps, on the other hand, people will literally tear it away from me, I have to drink it! It’s amazing! How can I get some! I’ll buy a whole box! … an immediate genuine reaction, which is completely rewarding. I keep joking about winning these medals which, of course, I don’t take too seriously, but sometimes it’s good to get some kind of objective opinion about what you’re making. It’s quite difficult to know for sure because my nose is not so elaborate—I can evaluate books a lot better than I can schnapps—so it’s important. Being dilettantes doesn’t stop us wanting to make schnapps at a very high level.

SB: But is that “high level” equivalent to publishing with Revolver? … I mean, in relation to what you were saying about creating a context which doesn’t exist already—a space, aura, position, community, or however you want to describe it.

CK: With the alcohol it’s a bit different, because the traditions are already in place. Unless I made a completely new schnapps, which is virtually impossible, the only thing I can do is give it a new context, with regard to how we make it, then how we present it—to indicate signs of a science, or craft … of an alchemist tradition and the sheer effort involved. We use old techniques and believe in associated ideas of purity, anyway, so this way of working fits with the general interest in organic production of recent years—usually in relation to the production of fruit, the slow food movement and suchlike. The only thing I can try to do with the schnapps itself—outside of its presentation—is produce objective quality. That’s the big difference to the book, because if you want to read one of the art books I’ve published you have to have studied art history. If I gave any of these books to my farming neighbors they’d immediately ask, how the hell do you make a living out of this? They wouldn’t understand it because they don’t know about art.

SC: And you don’t have to have an education in alcohol to get the schnapps.

CK: Exactly, you simply don’t have to be an expert. Of course there are schnapps experts and it’s good if they like it too, but ultimately it’s about this immediacy of you being able to say, yes, I like this one, or no, I don’t like that one so much. Both responses are fine—it’s the visibility and immediacy of the reaction that matters that makes the difference.

SB: I guess it’s similar to the immediacy of theatre or performance, as opposed to architecture or fine art, where you’re working with and on people and emotions in realtime—you can sense the atmosphere, tell if it’s going well. Also, with performance or alcohol, once it’s done it’s gone. The effect might linger, but the art itself is transient, remembered. It turns into a memory—and maybe a hangover.

CK: Although I don’t like theater so much for other reasons, I do think it’s a more honest medium than art, which I always feel is so complicated. There’s almost no chance to enjoy art on a very simple level anymore—maybe once in a hundred occasions—because most of it requires thinking about hierarchies and strategies: why is this here, how did it come together, who’s the curator, why is he working with him or her, blah blah blah. In a certain sense, theatre is simply about whether the audience is being entertained or not.

SC: Are you saying that theatre is essentially concerned with delivering a work to an audience where art is more … one on one?

CK: No … not one on one … because art can easily exist without spectators, without an audience, and often does. So it’s more like one on no-one. But I do mean theatre is closer to entertainment. Someone’s telling a story and someone else is enjoying it, where art is so much more … well, what can you get from it today? Value, investment, fame …

SB: Surely more than that. Last year I heard a speaker deliver a bullet-point teleological history of conceptual art, and the manner of presentation was Art’s Greatest Hits—incredibly condensed, but also arrogant and didactic … Ryman did this, then LeWitt did this, then Buren did this, and so on. Something very rich and complex was reduced to a cross between a relay race and the Eurovision Song Contest. Later on another speaker thankfully contested the violence of this presentation: the point isn’t that Ryman suddenly does a white painting, everyone cheers and ticks white off the list then looks for the next thing, but rather the shared fascination in observing someone going through the intellectual processes that lead to this or that physical embodiment of it—lectures, texts, paintings—to produce artefacts that map ways of thinking. Surely this is what art can offer, at the very least.

CK: Yes … but not in the least. It’s the opposite: in the best case. That’s what I meant to imply.

SB: So with regard to art in 2007 you mean there’s so much between you and the wall, so much to get through before you can get to the work … to such an extreme that work is in danger of short-circuiting itself, of stalling the audience in its slowness? To reframe the question slightly, why are certain novels—surely the slowest of mediums—so comparatively compulsive, so engaging, in a way that exhibition art so rarely is?

CK: I read maybe a hundred books a year, so two a week, but almost always pocket books, crime stories, definitely not high literature. Once you’re through with a few hundred, you’re done, so you have to dig harder for new names and even more inferior stuff—but for me it doesn’t matter, I’m still completely into the new inferior book in exactly the same way as the good ones. I would never do this with an art show. If I was in New York, say, and I’d read that gallery such-and-such had an exhibition of so-and-so, I’d never go … only if I already knew the gallery or the artist, that they’re doing good things, whatever that means. But where does that knowledge come from? It’s the same as the aura I mentioned with Revolver: in the end it’s all about biographies. As odd as it might sound, in 2007 biography is art’s primary form, in the same way that a specific style of narrative is to the crime story.

SB: Howard Singerman sums this up very succinctly in his book Art Subjects. He compares two art magazines, one from the 1940s and one from now, where the text on the cover has changed from being a list of subjects or techniques, to a list of names …

CK: Yes, that’s exactly what’s happening, but again, why is it happening? Personally, I think it’s precisely because art has become so complicated. It’s so thoughtful—that’s the irony—because artists aren’t just dealing with formal solutions, with overarching general projects, but with specific research and definite subject matter …

SC: Has contemporary art become too thoughtful, or too specific?

CK: I wouldn’t qualify it like that, I just think it’s ironic. I like art myself which is para-scientific, which contains information I might be interested in anyway, but is examined in interesting ways, with different parameters and techniques to those usually used by scientists, journalists, or whoever; work which has been researched in new ways. At the same time, I can see that this is problematic, because it requires a lot of texts and therefore publications in advance of any exhibition—or, better, a curator standing next to you explaining what you’re seeing, otherwise you can’t work it out or make the connections. I always find myself using the example of that piece by … shit, I wanted to say Oscar Wilde! … [long pause ]

SB: Henry Moore?

CK: No! [laughs ] … the dandy … [claps ] … Cerith Wyn Evans! … and specifically, his vertical ray of light in Venice. It’s a perfect example of something you can never understand unless someone tells you everything about it, then it’s completely interesting. If you simply stand in Venice and see a vertical light beam, you’d just think it’s just from some shitty provincial disco. Anyway, as a backlash to that kind of thing the only thing that’s really interesting otherwise are the names. I don’t mean to be cynical here, even though I know it sounds that way—but the main interest now is how someone got in this magazine, why certain careers are successful, what did they have to do to get there, and so on.

SB: As an art in itself, you mean? The social aesthetics … the mechanics …

CK: Yes, and you see this total change very transparently at the art schools, where I generally go to tell or teach something about books and their relation to art. Increasingly, the students already know exactly what they want, how to use them, the networks, what kind of aspect of their work has to be reproduced, what kind of context it has to appear in.

SB: Again, Singerman captures this very well, describing how in contemporary art schools students aren’t taught how to make art, as such, but how to be contemporary artists. This is an important distinction because totally based on an existing, exterior model, rather than forging a new, interior one. Ultimately that has to have a limiting or homogenising effect.

A bottle of clear Williams Pear schnapps is opened and poured

SC: How did you end up out here living and distilling schnapps on a farm in the middle of rural Bavaria after living in Frankfurt? Earlier, you mentioned being fed up with the art world—were you actively or symbolically dropping out of it by moving here?

CK: Well, one of the main reasons for giving up the publishing was through being increasingly involved with all the subventioned publications I mentioned. Making books with so many vested interests and the control that the commissioning institutions assert—at whatever level up the food chain—simply tends to result in books that people don’t really want or need; books without reason, or perhaps soul is a better word. So the publishing wasn’t very fulfilling, intellectually, and at the same time we were typically dreaming of moving to the countryside like everyone else. We loved the idea of slowing down life, especially with regard to the children, to give them an alternative to metropolitan living, with animals and food you could see growing—if they wanted, not dogmatically. Then we found this farm in a newspaper ad which, among the usual details, contained this phrase “right to burn.” We had no idea what that meant—it might as easily have meant the house was only good for firewood!—then we discovered it referred to the distilling rights which came along with the property. In German “distilling” comes from Brennen, which means “to burn,” because you’re essentially burning produce. So we came here, saw the distillery, and the former tenants explained that it was only used to distill wheat, which is what most of the farmers round here usually do. That’s how you make the most alcohol—it doesn’t cost much to produce and pays the most money. A hundred kilos of wheat costs five Euros at the most. We were just talking about subvention in European art, but that’s nothing compared to subvention in European farming, which is virtually total and so extreme that it’s getting to the point where, of course, farmers don’t care what they harvest any more. It’s not important to them because they only get money for the surface of what they’re cultivating.

SC: So it’s purely quantity over quality …

CK: Yes, and also at the moment they get money for grain if they bring it to the bio-gas facilities where they burn it for energy. Farmers get more money for burning it as fuel than for bringing it to a mill to produce flour. Anyway, we discovered that you have to distill at least every third year or you lose the right to do it, so we decided to go ahead and learn. I read a lot about it, which I wasn’t anticipating, but it quickly became very interesting. Perhaps that’s the law of dilettantism: as soon as you start getting interested in something by reading or researching, it automatically gets more interesting, a self-generating energy. Obviously there are a lot of connections between producing alcohol and art because its the same form of experimentation, it’s a research-based activity, it involves knowing a lot, doing a lot, and acquiring experience because you can always improve. It’s also very time-consuming … but in the end it’s fundamentally a beautiful alchemistic process which turns this pile of rotten fruit into this pure white—no, transparent—liquid that smells and tastes fantastic. My fascination with distilling is that it’s such an old technique—4,000 years old, maybe even 10,000. If you think about the fact that a bunch of people had this idea to heat something up and separate the different evaporation points simply to see what they get from it … such a simple technique and in the end it produces this form of magic.

SB: And it’s more satisfying working with a bunch of apricots than, say, Jonathan Meese?

Prolonged laughter

CK: Yes. Well, no, actually … it was also great to work with Jonathan Meese, I have to say. Funnily enough we actually just made a Jonathan Meese wheat schnapps for a bar he’s making in the house where Marx was born. But, yes, it is a lot more satisfying and interesting working with fruit farmers than all the various parties usually involved in subventioned publishing, that’s for sure.

SB: This implies that some or all of the dissatisfaction of working in publishing we‘ve been talking are solved—or resolved—by working in alcohol. Is this because the distribution of labor hasn’t changed in the same way? Perhaps the print industry could be described as having changed from “The Black Art” to “The Transparent Art” … which is odd as you just referred to alcohol’s transparency in the opposite sense, as a positive thing. I mean “transparent,” of course, with regard to the effects of desktop publishing, namely the availability and affordability of hardware and software, the so-called democratization of what was once a professional trade to a point where it doesn’t really exist anymore, or at best in a fractured, barely recognisable form, and the related sense that anyone can do it and everyone can see how it’s done; the outcomes being the familiar tropes of our condition—lack of specialization, blurring of roles, transient labor, et cetera. All of which follows the logic of advanced capitalism, but with a resultant chaos and anxiety which is proving a very difficult place to work from, a very unstable place, especially if you can still recall an earlier era where roles were more comfortably demarcated. Anyway, my question [laughs ] is: do you have a sense of reclaiming something that was missing by the end of Revolver by experiencing an industry still as controlled and traditional as alcohol production in the manner you practice it here, where the labor processes and roles remain distinct, perhaps emphasized by the small scale, the isolation, the interest in the alchemy … it all seems much more … human-sized.

CK: Absolutely, but also, as a book designer and editor you’re not the author—you’re more or less a service, and therefore only more or less involved. In producing agriculture, though, you are the author … although kind of from God’s grace … if you know what I mean.

SC: The apricot is stronger than you!

CK: Kind of, yeah. I don’t think of these things in terms of a big unchanging omnipresent creation, because these things can actually be modified, but still, I’m essentially working with material I haven’t invented—that’s the difference … and I have to find the people who make those things with the same love, because for sure 99% of the quality of this schnapps is the fruit, and only 1% is the art of the distiller. From good fruit you get good schnapps, from bad fruit you never do, it’s that simple. It might appear an isolated process, working out here on the farm, but it’s not at all … it involves a community and a network, and this is why I include these small texts on the bottles in addition to the obvious name labels, which go into some detail about the varieties of the spirits, and often include which farmer I got the fruit from, just to point out that you need these specific people to make this specific drink, and all are equally essential. But I like that idea of “The Transparent Art” so much because of the idea I keep mentioning about the objectivity—or the subjectivity!—and that’s the point!—in the end it doesn’t matter, both are the same with schnapps.

A bottle of Williams Pear schnapps (this time ripened in a barique barrel) is opened and poured

CK: There’s one other thing I can try and relate very quickly, and that’s something to do with coming from a city to the country with no prior relation whatsoever to farming, which is best described as a fascination for the utterly out-of-balance economy of nature, which is unlike anything experienced in a metropolis. Take the salad we were just eating, for example. If I calculate my hours in the sense of what we think of as a regular fee for labor, or even minimum wage, it would cost something like $30, accounting for the time I spend in the greenhouse, seeding, caretaking, and so on, and the same with the animals—so it’s completely out of balance with any way of economic thinking we’ve grown up with elsewhere. On the other hand it’s such a great feeling to actually do this work, even when it’s bad, if it’s raining or I’m tired, or things are going wrong … and in the end I work a hell of a lot for a tiny little bit of food. Again, on paper, it’s financially crazy because you could go to the best top-quality organic supermarket and buy this salad for much less …

A glass is knocked over and shatters

CK: Ah … sorry … but of course there’s some other quality which is less easy to define or relate—a feeling, a sense of rightness and equilibrium. It’s very simple: I donate a certain part of my day to work for my food.

SB: It reminds me of something else. Remember when Jan Verwoert was here, talking about communities, and he began with this very simple idea that we’re a self-made community borne out of mutual sympathies—and this can apply equally to the magazine or Revolver, as it can to the farm, or any of its various microcosms of animals, plants, fruit, or schnapps. These are groups and relations formed for their own sake, not towards any explicit end or result except their own continued existence—and here I mean rather than existing towards an explicit capital-P Political or other capital-S Social end. This struck me as one of those notions which is so stupidly obvious that you can’t see it until it’s suddenly refracted through someone else’s words. I had a similar experience recently working in the basement bookstore. I suddenly felt like I realized for the first time what capitalism was—by which I mean not as an abstract system I’m vaguely conscious of being complicit in at some indeterminate remove, but in the light of a customer standing in front of me holding a book and asking how much it costs—at which point my reflex is to answer, whatever you’re willing to pay for it. It was quite a shock to be reminded in this way how value is arbitrary, to feel it rather than have it described by a philosopher or politician or journalist. I guess this is the same hands-on practicality you’re talking about with the farm—primitive in its obviousness but still embarrassingly revelatory [laughs ]. I’m not sure whether this is leading to a question—maybe only to another drink—but there seems to be some relation between all this: the community whose point of connection is simply a way of thinking, or a sympathy for the others’ ways of thinking, and the allocation of time spent preparing your own food, that describes a kind of circular, self-feeding energy. Again, not towards something else—not to sell, to decide, prove, or invent something, particularly—but to exist, to maintain, to continue, to sustain. It’s a circular rather than linear way of thinking. Money is essentially just removed from the equation, and the new equilibrium is a balance of other elements instead.

CK: It’s also crucially based in the present rather than the future or on some idea of an end result, an attitude concerned with the here and now, with effort and commitment. It comes back to the various art systems we’re involved in, which—particularly at the moment—revolve around this idea of only doing things because …—because someone else invites you to, or will pay you to, or because you’ll gain some perceived outcome … money, respect, fame, further invitations, whatever. The idea of getting together or making something without those preconditions is becoming increasingly rare, and that’s a shift for the worse. For me the reasons for spending time growing these things is also just a simple reaction to not being able to find value or satisfaction in other things. Today I can say I’ve never felt more satisfaction than when I spend an afternoon here in the stables, for example. Why should I spend so

much time doing things like publishing when I could also spend it generating food and drink for myself and family and friends? That feeling only increases, then becomes an obsession, because if you have a farm suddenly you’re bound to think about the idea of “land” which, of course, you don’t have to consider in the city. As an artist anyway, you’re now trained to live as flexibly as possible—don’t own anything, have your suitcase packed and ready—but if you’re on a farm one of the things you find you’re suddenly responsible for is the ground, very literally, with a heritage to consider. If we didn’t mow the meadows correctly the farmers next door would come and say, hey, this isn’t good enough—there’s an inherent ethos that the land has to be cultivated properly. Again, it’s simple and obvious, you own something and suddenly it’s important to maintain it. Owning becomes interesting again. Take livestock, for instance, which involves the responsibility for their lives, a completely different relationship to the possessions we’re used to. Spending time with the animals becomes a complex thing, because it’s not solely—or visibly, or immediately—about money. It doesn’t work in the same way.

SB: And the new value is a certain intensity of feeling?

CK: It sounds very kitsch but it’s very true.

SB: “Intensity of feeling” is quite clear in terms of the publishing and distilling, but less obvious in terms of ownership. It’s interesting to consider the idea of ‘owning things’ as being fundamental to both capitalism and your farming existence, even though we’re generally implying they’re opposites. Perhaps it’s the difference between the hollowness of gratification and richness of responsibility; you’re distilling the good parts of the idea of ownership. That’s pushing it a bit, but you understand what I mean.

CK: Yes, again it’s to do with taking care of things. I’ve never really spoken about this with anyone before, but sometimes I need two hours in the evening to just walk around and look at everything … and though I’ve seen it many times, it’s nothing to do with pride, it’s simply about watching … looking properly … what happens over here, what happens over there … those plants are dying now, those plants are growing … the tiles have come off the roof here … just checking the status of things. It’s almost embarrassing to describe this walk, but that’s what happens; it’s a strange level.

SB: It’s getting late. Maybe we should talk about labels on the bottles, seeing as we’re pretending that’s the reason for the whole conversation.

CK: Okay, but let’s taste the most uncreative one first. This is the basic wheat schnapps made from pure grain.

A bottle of Doppel-Korn wheat schnapps is opened and poured

CK: This is only wheat and yeast, so it tastes like bread. That’s what people drink in huge amounts in the north of Germany, if it’s cheaply done—this is the one for getting drunk, to slowly kill yourself, basically. If distilled well, with care, however, it can also be very tasty. So … the labels. Our basic idea is to create a product which is nurtured and nutritional, made slowly, with craft, how most people imagine the ideal of food and drink, as organic, homemade, hand-cooked, and so on. In this case those ideas are very extreme because every single stage involves this kind of attention. We harvest the fruit, then crush it, and often we mash it by hand rather than at a mill because we believe this process retains more of the aroma. Also, if a lot of the cores break they release a poisonous blue acid, so I stand there for, say, five hours at a time, squashing the fruit in my hand. This is where all the knowledge of enzymes, chemistry, acids and different kinds of yeasts comes in. Because scientists isolate and introduce new enzymes all the time, there are always new kinds of movements going on, splitting the fruit in different ways which yield different aromas. Basically, the mash should be as liquid as possible. The aroma molecules attach to the alcohol elements, so the more liquid they are the easier they can get together.

SB: Like any Friday night in any community …

CK: We then want to make it clear that this is how we’re distilling: traditionally, slowly, with this much care and attention, which is where the labels come in. They’re deliberately conservative. All the people from the clubs and the official-professional side of schnapps absolutely hate my labels.

SB: But they’re “conservative” in quotation marks, right? Self-consciously conservative, I mean.

CK: Well, more neo- or post-conservative, I would say. Does something like “post-conservative” even exist!? [laughs] On a “good” schnapps label according to the schnapps people, there has to be a photograph of a fully ripe fruit and golden lettering.

SB: Which is surely conservative without quotation marks. Isn’t yours is a style, a signifier, rather than being conservative …

CK: Not exactly, no. I would say that those guys with the ripe photos are betraying our tradition in the sense that, in my opinion of what schnapps is and means, the heritage, they really should look like this—like ours—in some way.

SB: Ah, you mean in the same way as the tradition of the baseball outfits, whereas the ripe fruit labels are more like soccer kits?

CK: Ha! Exactly, yes! A good soccer kit should just have those socks with a couple of stripes, single color shorts, and a plain matching top. Conservative—like I said! With some of the varieties, though, the labels also refer to a specific historical period. The high time for corn schnapps was after the First World War until a little bit after the Second World War, for example, so we used these particular period vignettes; then the Green Widow Absinthe has this strange Art Nouveau label for obvious reasons. Sometimes we even make these references through the language … for example the term Deutsches Erzeugnis, meaning “German product,” which has it’s own strange history. Before the mid-nineties it was mandatory to include that on the bottle, but now the connotations are more Nazi than anything else, and is also completely crazy considering the EU, especially since these are all very obviously local products and everybody knows we only really sell them in this area. So we play with that, or similarly “Agricultural product” because if you’re a bona fide distiller you have to include that to distinguish from industrially-produced schnapps. Of course the joke now is that the industrial distillers try and make their products look as agricultural as possible—with a little farmhouse on the label, and so on. So we use particular text, particular typefaces and so on. The only other condition for the labels is that they also have to be fit to be printed out on my laser printer! [laughs ]

SB: So you’re really back to the first days of Revolver …

SC: And the bottles are sold locally?

CK: Well, I’m not legally allowed to export them because all us distillers have some kind of tax reduction. It’s not actually that true, but that’s how it’s described.

SB: And what are the percentages of distribution like, including the government?

CK: In the case of, for example, the wheat schnapps, 60% goes directly to the government.

SC: 60%!?

CK: Yes, that’s the tax. The whole system is completely feudalistic: the rules are based on something written in 1830, then written again in 1937, I think … and it’s still the law. A feudal system basically means you’re allowed to distill, but the state has the monopoly, and you’re tolerated as long as you supply most of it as a proportional tax: we let you make so many litres a year as long as you give us so many litres a year.

SC: And what do they do with it?

CK: They sell it to pharmaceutical companies, who refine it, neutralise it, and use it for medicine. Obviously you don’t do this with expensive fruit schnapps—you pay tax with the wheat and apple schnapps, or in equivalent money, which is also possible. I can’t export internationally, but I can sell it in Germany. Otherwise, at the moment, apart from local restaurants, most of the sales are actually from the art crowd buying it through word-of-mouth. If they buy one, they buy six more, and so on. We’ve just made a deal with one bigger place who’ll buy 200 bottles at a time, then we’ve done a few artists editions. Before we finish with the absinthe we should make a short detour and try this likör, which is traditionally the ladies’ drink, made from herbs, and which doesn’t contain much alcohol; something like Ramazotti or Averna.

A bottle of Artemisia Goldbitter, a herbal likör, is opened and poured

SB: You did an interview a while back with Maria Fusco about teaching, in which all your responses were lines from your cheap crime stories …

CK: Yes, she re-used a questionnaire by Paul Thek from the 1970s or ’80s. They were questions which he put to himself, I think …

SB: Right, and as far as I recall, your replies, or maybe the footnotes to the replies, related your belief that teaching should be founded on teaching specific craft skills rather than personal development, or let’s say what have become the more psychiatric tendencies of contemporary art teaching.

CK: Yes, though I would call them “methods” rather than “skills.”

SB: But was this a straight response? I remember I’d forgotten your answers were actually quotations, and then couldn’t work out whether they genuinely reflected your own views.

CK: The actual answers to the main questions—the detective quotes you mention—didn’t mean anything. I mean, if you’re Paul Thek—the most esoteric idiot you could imagine—they could mean something because they could mean anything. The only serious response in terms of what I actually believe in are in the footnotes, which are about the “methods” you’re talking about.

SB: I’m trying to formulate a related question in light of all we’ve talked about, but I’m not sure what it is. Can you make one yourself? [laughs]

CK: Well, those answers were tied to a very specific experience. Through a few strange events I became a professor at an art school in Hamburg, which as you know is a big deal in Germany because it’s well paid, you’re working for the state, they can’t fire you, and so on, a bit like tenure in the US. Anyway, that school is very much based on ideas of the 1970s, so everything is “anti-authoritarian”—in quotation marks again—all about “building personalities.” The students they take on are very young … 18, 19 … usually directly from school, and naturally they have no idea what they want to do, no idea what they want from you, from life, and your job is to “build these personalities” … it drove me crazy.

SB: That’s the school’s explicit mandate?

CK: Well, first you get a lot of literature, as a teacher, then you meet the others who have been there for 30 years, with the beards and all that, and then they tell you, this is what we do and how to do it. So of course the first thing is to say well, I don’t believe in that so I’ll do something different, but after only one year I was so frustrated because nothing was moving. I remember one girl, typical of this situation, who was in a band. The whole time she was there all she did was make posters for her band … which was completely fine, just not art, in any sense whatsoever. My response, however, was immediately ignored in light of the overriding idea that this was part of her personality! So what!? I couldn’t see why I was supposed to be teaching them—I don’t know—ethics, morals, character. There was no objective criteria whatsoever, and of course they had no time for grading or evaluating. This is what I meant about the Paul Thek questions—they’re only about belief, which I just don’t see as relevant to art. I quit after a year, and that’s what the interview response was based on. How’s the herb thing?

Silence

SC: It’s a little too much like medicine …

CK: Ah, too bitter! … let’s counteract it with a really sweet one, then.

A rogue bottle of Raspberry Likör is opened and poured

CK: This one’s not actually made by me but by a neighbor, Frau Braun. [Sips, considers ] Yes, it’s very … sugary. She makes some kind of syrup with raspberry juice and mixes it with neutral alcohol, unlike ours which is based on the ghost. This gets slightly complicated to explain, but basically we put the spirit of the fruit into it. There are two different ways to make schnapps. One is to distill the actual fruit, and the alcohol is produced from the sugar in the mash which carries the aroma with it—this is what is called fermenting. The other is to take neutral alcohol and mix it with the fruit. Instead of fermenting, the neutral alcohol sucks the aroma out of the fruit. The process used largely depends on the type of fruit, and the latter is better for raspberries. We’ve always used the first method, however, which involves the Geist—a beautiful word, because it means … well, yes, it means “spirit” … like “zeitgeist”—the spirit of the times.

SB: What about moonshine?

CK: [laughs ] What about moonshine? It has two meanings, right? One is the product, and one is the act of doing it. So which are you talking about?

SB: The act of doing it … to make the product.

Prolonged laughter

SB: Off the record.

CK: It’s actually very dangerous. Another part of this feudal medieval law is that the customs authorities have the right to check on you whenever they want, without notice. In former times they just went around the mountains in October looking for smoke from fires, which usually indicated a distillery. They still check very regularly, though, and when they do they check absolutely everything—the storage, the day’s production, whether there’s any sugar added to the mash, which isn’t allowed, and whether you’ve produced exactly what you claimed you would. The surplus is what they call moonshine.

SC: Isn’t it called that because it’s made after hours, by the light of the moon?

CK: Yes, in the swamps in … [pause ] Mississippi [laughs], I don’t know. I guess it originally had something to do with prohibition, when you basically had to do it to produce anything.

SC: And for those who couldn’t afford the official stuff, so would just make it themselves. Basically it’s the rough stuff that gets you wasted fast …

CK: Yes, and that’s why I asked whether you meant the act or the product, because even if you distill black, cheaply, you can still make a reasonable, clean alcohol, a clean spirit. When distilling you have to make very clear divisions between the head (which is the pre-run), the heart, and the aftermath (which is called the “tail”) and has all these oils and higher alcohols which make it taste bad … but if you want to keep it all, to literally make the most out of it, you simply mix it all together, in which case you also have this very unhealthy thing, which is where all the stories of people going blind come from.

SB: So you’re saying it’s possible to be moonshining and not actually make moonshine, and also to make moonshine while not actually moonshining?

Hysteria

CK: Actually, I’ve been fined already for moonshining … because in the end distilling in Germany is, officially, all about money too. One day I was busy distilling 2,000 litres of mash, and they came to check up. I’d applied for this quantity, so it was all fine, then they checked the tanks and in the end, after three hours, they said, well we checked your tanks and found you have 2,060 litres in there instead of 2,000. I said it couldn’t be—this was mash from Hungary which came with an invoice saying I bought precisely 2,000 litres, and they say, yes, yes, but we measured it and it’s 2,060. I was so convinced that I refused to accept it and demanded that they prove it, to which they replied, well, to prove it we have to open the tanks and basically destroy the whole lot. So that’s that, I’m caught even though I didn’t do anything. Then they fined me for the extra 60 litres and the penalty was 22 Euros! … so obviously this was just a symbolic fine, a yellow card. Next time it gets more serious—a red card and I’m off the pitch. It’s essentially a system which is out to kill the small industries, like everything else.

SB: Any last thoughts before we start on the absinthe?

CK: Maybe I should just say that, in relation to the surface of what you’re interested in here—the change from publishing books to publishing alcohol—I have to confess that my involvement has also changed my idea of what design and designing is, and that’s also precisely in terms of thinking about it less as a surface, and more towards to the notion of changing material from one form to another. By the end of Revolver I could maybe understand the idea of designing being an act of transformation, of translation, or transposition, but now I understand it more clearly—more transparently—through observing the tangible changes from plants and fruit to other forms.

A bottle of Grüne Witwe, a traditional Absinthe, is opened and poured

*